I visited southern coast of Spain, Gibraltar, and the coast on the Atlantic side of central Portugal (also known as the “Silver Coast”) in the spring of 2024. The scenery is beautiful and its sedimentary rock structure is particularly special.

Strait of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar separates Europe and Africa, with its narrowest point of only ~14km / 9miles wide. We lucked out with perfect weather the whole trip, giving us a clear view of both shores.

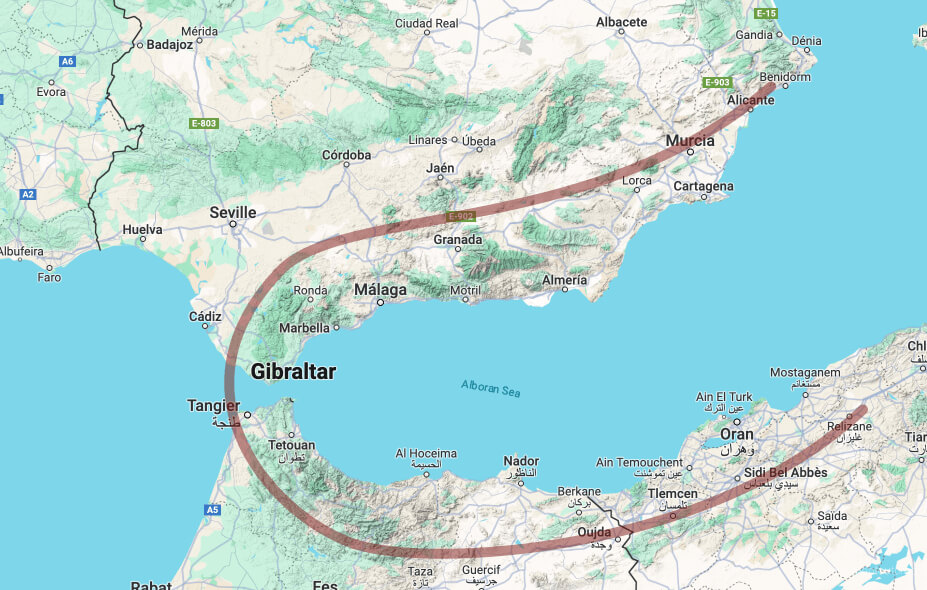

But geologically speaking, the boundary between the Eurasian and African tectonic plates isn’t actually at the Strait of Gibraltar; it’s further south. The southern coast of Spain, Gibraltar, and northern Morocco together form a horseshoe-shaped orogen known as the “Gibraltar Arc.”

The Cordilleras Béticas mountain range, home to the highest peak in the entire Iberian Peninsula, Mulhacén, is indeed part of the Gibraltar Arc.

Right: Before landing in Malaga, you can spot the rugged mountain ranges rising up ahead.

About 5.95 million years ago, the Gibraltar Arc blocked the connection between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea, triggering the Messinian salinity crisis. This continued until about 5.33 million years ago when the land bridge in the middle of the arc- now the Strait of Gibraltar- broke apart, allowing Atlantic waters to refill the Mediterranean and establish the connection until now.

The name “Gibraltar” comes from the prominent limestone rock found in British Gibraltar territory. It originates from the early 8th century when the Berber general Tariq, who departed from North Africa to conquer the southern Iberian Peninsula, named it “Jabal al Tariq” in Arabic, meaning “Tariq’s mountain.” Over time and through various mispronunciations by foreigners, it morphed into “Gibraltar.” The rock itself is made of limestone, with a gentle slope and vegetation on the western side where the town is also located. The eastern side features steep cliffs with minimal vegetation.

Gibraltar is such a tiny patch of land but with surprisingly intricate microclimates. It’s misty and hazy around 10 AM, with the eastern cliffs visibly trapping sea fog, while by around 1 PM though, not a trace of clouds or mist remains.

The rocks here still bear witness to the Barbary macaques that arrived from North Africa long ago.

Inside the limestone mountains, there are quite spectacular caves with well-developed structures like stalactites, stalagmites, and columns.

Later, we took a ferry to Ceuta in Spanish North Africa. We could see Jebel Musa in Morocco on the way, which is twice the height of Gibraltar’s rock and part of the Rif Mountains- the southern segment of the Gibraltar Arc.

Right: Gazing into the panoramic view of Gibraltar from afar.

Looking back at Europe from Ceuta, the Gibraltar Rock stands out prominently.

The cultural and historical interplay between British Gibraltar, Spanish North Africa, and Morocco is incredibly complex, a story that could fill volumes. In essence, it’s a tale of “big fish swallowing smaller fish”. Initially, I wondered if Ceuta being in Africa and adjacent to Morocco would differ significantly from mainland Spain in customs and culture. Turns out, it’s quite similar. Portugal seized Ceuta from the Muslims in 1415, and it became a Spanish colony in 1580 after a change in sovereignty. So it’s been in European hands for about 600 years now- quite a long period of time.

In the 17th-18th centuries, Ceuta witnessed the longest siege in history, lasting 33 years, known as the “Siege of Ceuta.”

Cádiz

Before heading to Portugal from Gibraltar, we spent two days exploring Cádiz, a historic city in southern Spain. As the oldest continuously inhabited city in Western Europe, Cádiz has witnessed the rule of Phoenicians, ancient Romans, Moors, and Spain over the past three thousand years. The 18th century marked Cádiz’s golden age when 75% of trade between Spain and its American colonies passed through this port city.

Wealthy merchants and magnates of Cádiz favored using a local sedimentary rock called “ostionera,” for their mansions. Ostionera is a porous sedimentary rock formed by remains of seashells and eroded stones. Many buildings in the old town still retain this material, showcasing clear oyster shell patterns. Even the staircases in the old streets are made of similar materials. Located outside the Gibraltar Arc, Cádiz is situated in a low-lying, flat area that was once a shallow sea during the early Cenozoic era, resulting in abundant sedimentary deposits and rich fossilized marine life.

Right: The outer walls of the buildings in the old town of Cádiz are adorned with ostionera.

Right: The sedimentary rocks along the Atlantic Ocean coastline near Cádiz.

By the way, the journey from Malaga to Cádiz offers fantastic dining and chilling experiences. Locals love going out and we haven’t experienced over-tourism. The quality of seafood, cured meats, and red wine is exceptional. In addition, as a country mostly falls within the GMT time zone, Spain adopts GMT+2 timezone during daylight saving, which leads to late sunsets and late closing time of restaurants – perfect for owls like me.

In comparison, Porto and Lisbon feel more over-touristed (wait, I’m one of those tourists too).

Geoparque Oeste

Fortunately, the Geoparque Oeste in central Portugal is quite unknown for now and provides lots of free space to wander around. It was recently designated as a UNESCO World Geological Park. Its features include Jurassic sedimentary rocks and abundant dinosaur fossils. Our journey took us from Praia do Seixo to Praia de Santa Cruz, but we missed the chance to visit the Lourinhã area in the north, known for its dinosaur fossils and footprints.

Near Praia do Seixo, there are clearly layered Jurassic seabeds with fine-grained textures. Some areas feature yellowish conglomerate rocks at the top.

Heading south to the southern side of Praia da Vigia, you’ll encounter a plethora of colorful sandstone cliffs reminiscent of the beauty of Death Valley.

There are hardly any people around, making for a fantastic travel experience.

Further south, you’ll encounter the iconic “Penedo do Guincho” of the Geoparque Oeste.

The yellow turbidites are remarkably thick here, reflecting intense sedimentary activity in the past. On the cliffs near the Penedo do Guincho, you can clearly see the distinct boundary between the turbidites and the fine-grained seabed. The rock layers are severely tilted as well.

Lots of details to inspect as well if you look closely.

Looking along the coastline, the tilted layers of the seabed are clearly visible. In the photo below, as you move towards the right, the rock layers get progressively younger, with the yellow turbidites extending further right beyond the frame of the photo.

Not sure why but let’s conclude with a picture of the Bone Chapel in Évora Portugal!

Great write up and pictures! Super interesting geology

Loved reading about your observations that brought something I would have overlooked and gave it meaning and context. Can’t wait to read the next installment of Newfoundland!

Great job!