Yes! Among the three major types of rocks (igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic), metamorphic rocks might not be quite straightforward to identify – unless there are extremely distinct foliated textures. Recently I encountered some impressive metamorphic rocks in three locations in North America: Kings Canyon in California, Black Canyon of the Gunnison in Colorado, and Tablelands in Gros Morne National Park, Newfoundland.

Kings Canyon National Park

We visited Kings Canyon NP and Sequoia NP in the same trip. While Sequoia NP is famous for having the world’s largest trees (feel free to check out my other post about Sequoia NP), Kings Canyon maintains a reputation of being relatively low-key and undisturbed- with only 7% of the park readily accessible to the public. The dead-ended California state route 180 is the only way into the park.

Due to the rapid uplift of the Nevadan orogen and the efficient erosion by the South Fork of the Kings River, Kings Canyon is one of the deepest canyons in North America, reaching depths of up to 2,500m/ 8,200 ft. The South Fork flows from east to west, and before it reaches Cedar Grove, the canyon features glaciated granite landscapes similar to those found in Yosemite, showcasing pristine natural beauty.

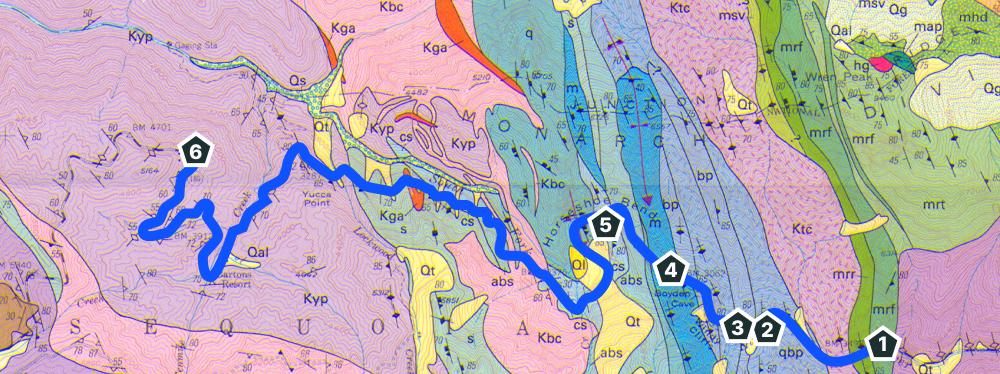

Heading west from Cedar Grove along CA 180, there is a particularly diverse and stunning stretch of metamorphic rock cliffs in the valley: from several turns before Boyden Cavern in the east, to Junction View approximately 18 kilometers (11 miles) to the west.

It was actually near location #1 (where the metarhyolite is) that we initially found the cliffs along the road started to look intriguing. We had no idea what type of rock it was until we came back home and looked it up. At that moment we were just struck by its vivid red color, the fragmented joint patterns, the abundance of moss covering the cliffs, and their overall picturesque appearance.

Before getting to Boyden Cavern, we could already see towering peaks of marble reaching into the clouds. Their textures and colors sharply contrast with the surrounding landscape.

Further along on the right-hand side of the road cut, there’s an exemplary exhibit of folded rock layers that were dramatically transformed, a clear indication of metamorphic processes. Phyllite’s pre-metamorphism parent rock was originally sedimentary rock like shale or mudstone. It’s hard to imagine how immense the pressure was when this transformation happened.

Boyden Cavern is a limestone cavern with mixture of marble (limestone transforms into marble during metamorphism). We didn’t have enough time to visit the cavern this time, but judging from online pictures and reviews- it seems worth a visit! On the steep cliffs opposite to the cavern, there are small streams that join the South Fork of the Kings River. It seems that the entire mountain here is composed of marble. If we look closely at the rocks in the water (bottom left corner of the photo below), we can see marble stones with intricate patterns- although they have clearly been smoothed by water erosion which made them less angular compared to the ones still up on the cliff.

Continuing westward, there’s a viewpoint along the road at location #5- Horseshoe Bend. This section of the highway is approximately one-third up the valley. Looking eastward and upward from this point, we could see the western face of the marble mountain range as a backdrop, with the foreground of schist formations that appear yellowish. The river is right below us deep in the valley.

irreverentoutcrop.com

The spectacular rock cliff directly opposite from the viewpoint has really epic textures. Upon comparing with the map after the trip, I realized it likely marks the boundary between quartzite and schist zones.

The viewpoint at Junction View (location #6) is significantly higher in altitude. Looking eastward from here provides a panoramic view of the joint of the South Fork and the Middle Fork of Kings River. The mountainous terrain exhibits rich layers, and the rivers cut deeply into V-shaped valleys. Nice weather and lighting conditions certainly further enhance the beauty of it.

Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park

The Black Canyon is located deep in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado. We visited it in late autumn.

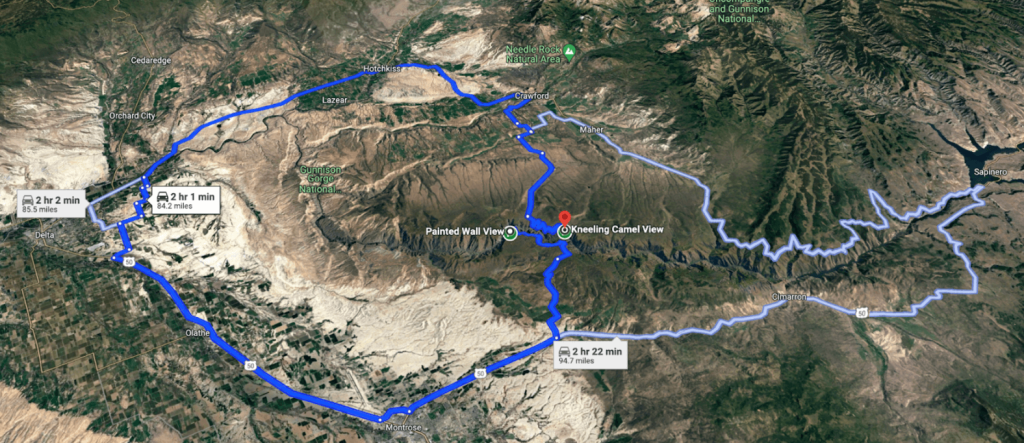

This national park is relatively less known within the big family of US national parks. It occupies only a narrow piece of land and it’s hidden in the mountains with somewhat limited access, which has historically kept visitor numbers low but definitely enhanced the experience for those who do visit. On our journey from Denver to Mesa Verde, we stopped along the southern rim of the Black Canyon, and on the return trip, we took a different route to explore the even rarely-visited northern rim. The canyon’s southern and northern sides are not connected directly- reaching one from the other requires a detour of at least two hours one-way.

The country rock of Black Canyon primarily consists of extremely ancient gneiss, accompanied by schist, both of which are metamorphic rocks with a deep gray color. These formations date back approximately 1.7 to 1.9 billion years ago- even older than the bottom layers of the Grand Canyon. The irregular streaks of light salmon color represent later intrusions of granite, around 1.4 billion years ago.

Among the interplay of different rock patterns, I think the Painted Wall View is likely the most spectacular vista in the entire canyon.

Other view points offer different angles of the valley.

The country rock dating back over a billion years is indeed remarkably ancient, considering that the Cambrian explosion occurred about 550 million years ago. However, it wasn’t until about 60 million years ago- after the extinction of the dinosaurs- that this region began to uplift. River erosion did not even begin until around 2 million years ago in the Quaternary period, with an erosion rate of approximately 2.5 cm/ 1 inch every 100 years. Relatively speaking, the canyon’s development is still in its youth, maintaining a distinct V-shaped profile with steep cliffs on both side- particularly on the north-facing cliffs of the south rim of the canyon due to more severe ice and snow erosion. Some sections are nearly vertical. The canyon bottom has yet to develop significant meandering, and the river remains relatively straight and narrow.

The deepest part of the canyon reaches 829m/ 2722ft – taller than Dubai’s Burj Khalifa, and twice the height of the Empire State Building.

After exploring the south rim of Black Canyon, we continued south towards Mesa Verde. On our way back, we took a different route to the north rim. The weather in autumn was unpredictable especially in the mountains, and we encountered heavy snowfall along the way.

The alpine lakes adorned with a blanket of white snow have a unique charm of their own.

irreverentoutcrop.com

When we returned to the northern side of Black Canyon, we found that there weren’t even proper entrances. We drove through a small town and a series of dirt roads, and suddenly we were there. The snow had just stopped, and we were the only car at the north rim, surrounded by an unusually quiet atmosphere. It was only two days since we were at the south rim, but the snow made the vibe of the canyon completely different.

The stripped-away columnar structures are schist.

The snow just stopped, leaving a soft and thick layer covering the area. Various wild animals eagerly left their footprints behind.

Tablelands (Gros Morne National Park)

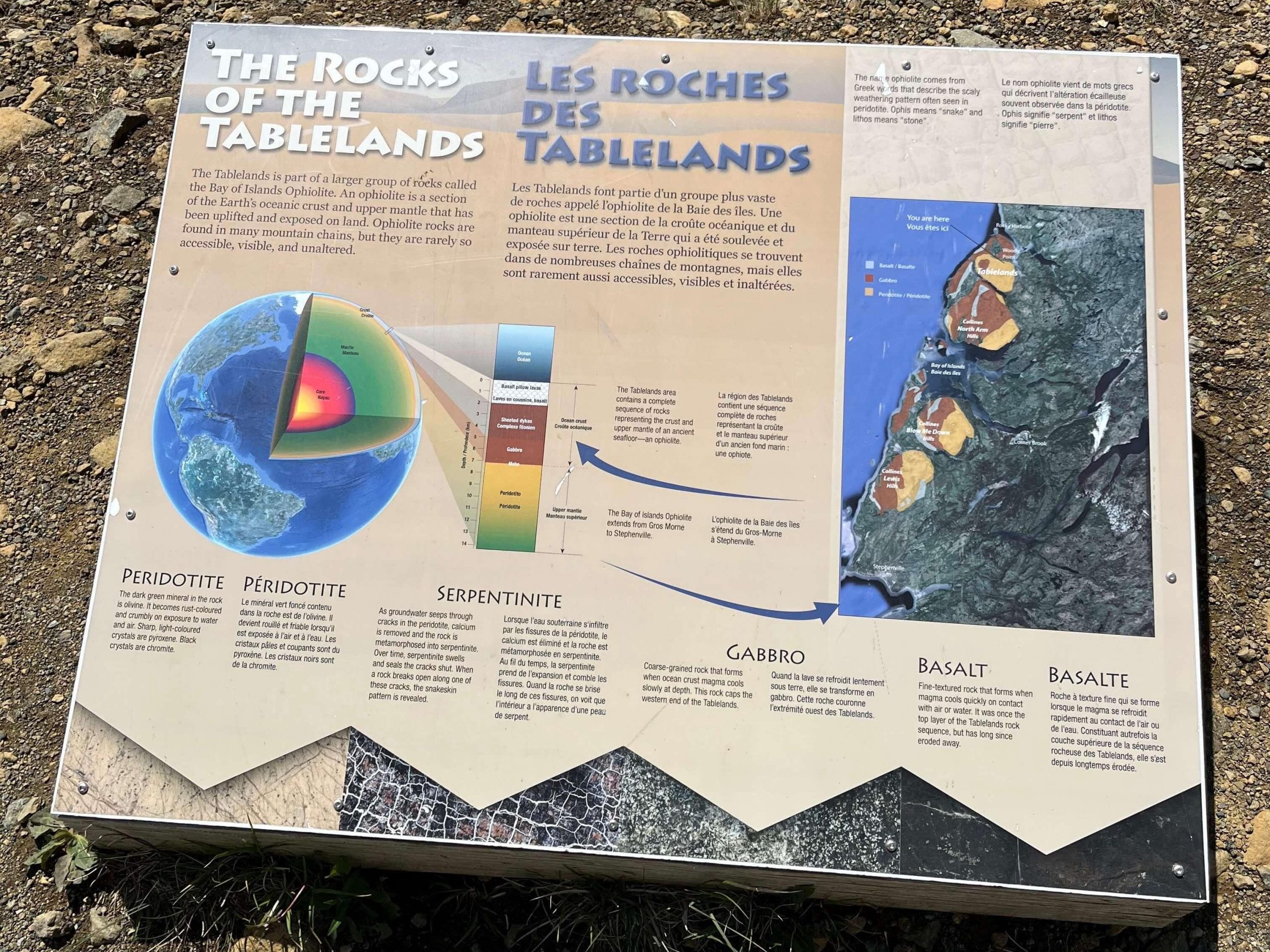

During our visit to the Tablelands of Gros Morne NP on the west coast of Newfoundland in summer 2024, we encountered a relatively rare metamorphic rock called serpentinite.

Serpentinite originates from peridotite – which is rich in olivine (Mg,Fe)2SiO4 and a primary component of the Earth’s mantle but rarely exposed on the surface (well, because mantle is beneath the crust). It’s only when certain tectonic movements crack-open a rift to bring mantle out that we can see it on the Earth’s surface. Newfoundland’s Gros Morne NP and Macquarie Island – a tiny island halfway between New Zealand and Antarctica – are the only two known places in the world where mantle is exposed above sea level.

The metamorphism of serpentinite does not occur due to deep crustal pressure but rather through hydrothermal activity. Therefore, it can only be seen on the surface of the Tablelands, a process known as “serpentinization”. This process involves the reaction of olivine with water, causing its volume to expand and resulting in the formation of cracks. The color darkens, creating a network pattern on the surface of deep green serpentinite. As an exothermic reaction, the heat released from this reaction, along with the extra surface provided by the developing cracks, further accelerates the reaction.

As a significant hydrothermal process, most serpentinization reactions actually occur at mid-ocean ridges—where magma erupts and reacts with surrounding seawater. Under certain conditions, this reaction can release hydrogen and methane, influencing seafloor fluid dynamics and ancient biological activity. In June 2024, NASA reported that recent studies of rock samples from the asteroid 101955 Bennu suggest that Bennu may have even split apart from an ancient ocean world. One compelling reason for this hypothesis was the discovery of serpentinite in its rock samples, indicating past interactions with water which was necessary for its formation.

Gros Morne NP is a large park with a variety of nature and geology wonders. The area where we could see serpentinite is only a tiny part of it. I will cover more about Gros Morne in my future posts.

P.S.: I found interpretive exhibits in Gros Morne NP really well done in terms of presenting knowledge—they’re highly scientific and never delve into cliché things like this rock is shaped like a lion’s face or that rock looks like a camel. They’re also rich in visuals and explanations that are accurate in science but easy to comprehend at the same time.

Theoretically speaking, Death Valley, Joshua Tree National Park and many other places also have a large amount of metamorphic rocks, but I didn’t pay enough attention when I was there before. I’ll do better when I visit them next time!

irreverentoutcrop.com