During our March 2025 trip to Kaua‘i, Hawaii, one unforgettable day stood out: we spent seven hours soaking in the breathtaking vistas of the Nā Pali sea cliffs, the volcanic Lehua tuff cone, and the remote shores of Ni‘ihau—often called the “Forbidden Island”.

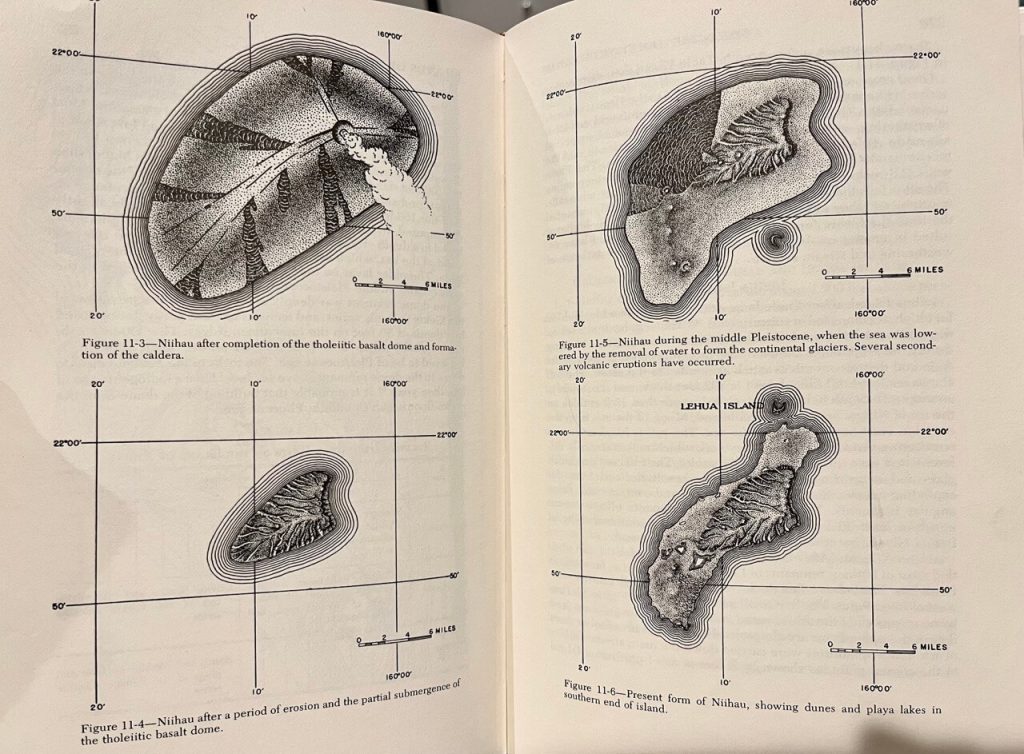

Over the past several million years, magma from the Hawaiian mantle plume hotspot has continuously erupted, while the Pacific Plate has been moving northwest. The combination of these two processes has formed the Hawaiian Islands—the portion of the hotspot trail that rises above sea level. Kauaʻi and Niʻihau, the farthest from the hotspot, are the oldest of the islands, having formed around 5.5 million years ago. As for the background knowledge on hotspots and tectonic plates, extensive resources are available online so it will not be elaborated here.

‘okina

A special note on the Hawaiian language’s use of the single quotation mark ‘ (formally recognized in the Hawaiian alphabet as the ‘okina), which indicates a glottal stop or syllable break. For example, when this mark appears between consecutive vowels, the vowels are pronounced separately rather than as a diphthong/”vowel glide”.

Sea cliffs of Nā Pali

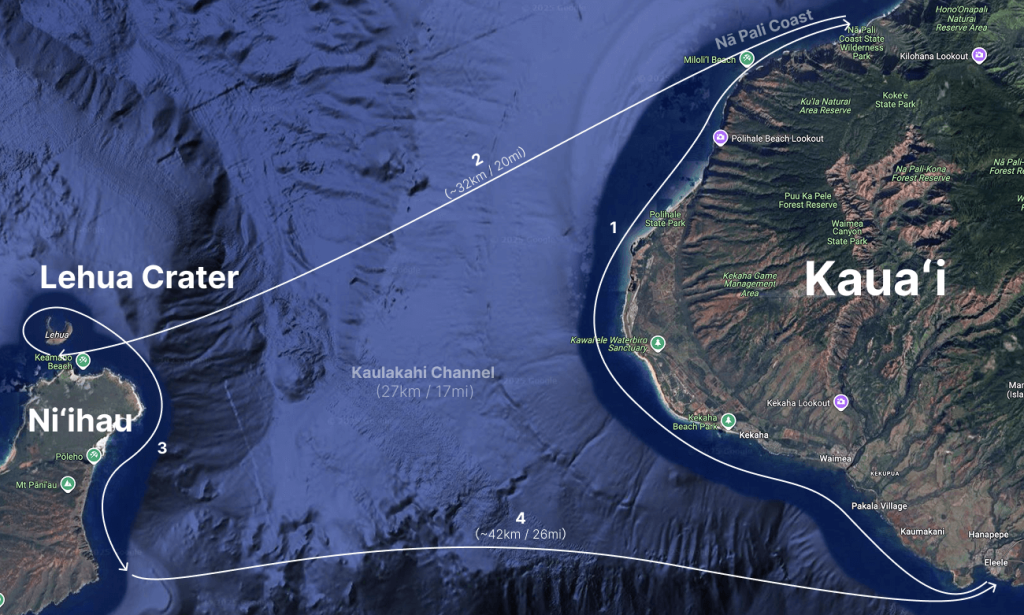

Our day began at 6 am with a checkin at Port Allen in the town of ‘Ele‘ele. While over a dozen tour operators on Kaua‘i offer 4-hr round-trip excursions to the Nā Pali Coast, only two companies have the option to include the additional journey to Lehua and Ni‘ihau, extending the trip to 7 hours. The Nā Pali Coast, located on Kaua‘i’s northwestern side, actually offers better photographic lighting in the afternoon. However, the 7-hour Ni‘ihau combo tours typically visit Nā Pali in the morning.

After leaving the harbor and passing a U.S. military missile base near Kaua‘i’s southwestern tip, we soon glimpsed Nā Pali’s iconic sea cliffs. Fittingly, “Nā Pali” itself means “many cliffs” in Hawaiian language.

Kaua‘i’s ocean island basalt (OIB), like that of other Hawaiian islands, originates from the same mantle plume hot spot. However, prolonged erosion and oxidation have given its soil and rocks a distinctly redder hue compared to other Hawaiian islands like Oahu, Maui and the Big Island. The volcanic formations along Nā Pali—classified as Waimea basalt—mirror those found in Waimea Canyon, underscoring their shared geological heritage.

The several beaches we passed along the cliffs, such as Miloliʻi Beach, are all open for overnight camping. However, since there are no land routes, the only way to reach them is by boat or canoe.

As the captain steered closer to the cliffs, we observed intricate igneous rock details on the cliff faces, including elongated intrusive dikes. Signs of wave erosion were unmistakable—sea caves and wave-cut benches dotted the coastline.

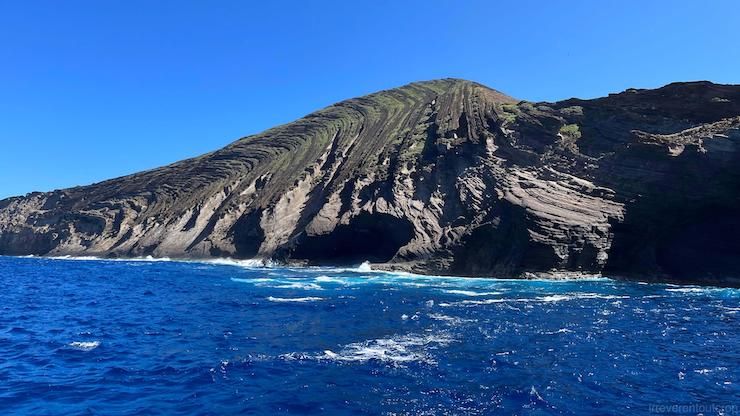

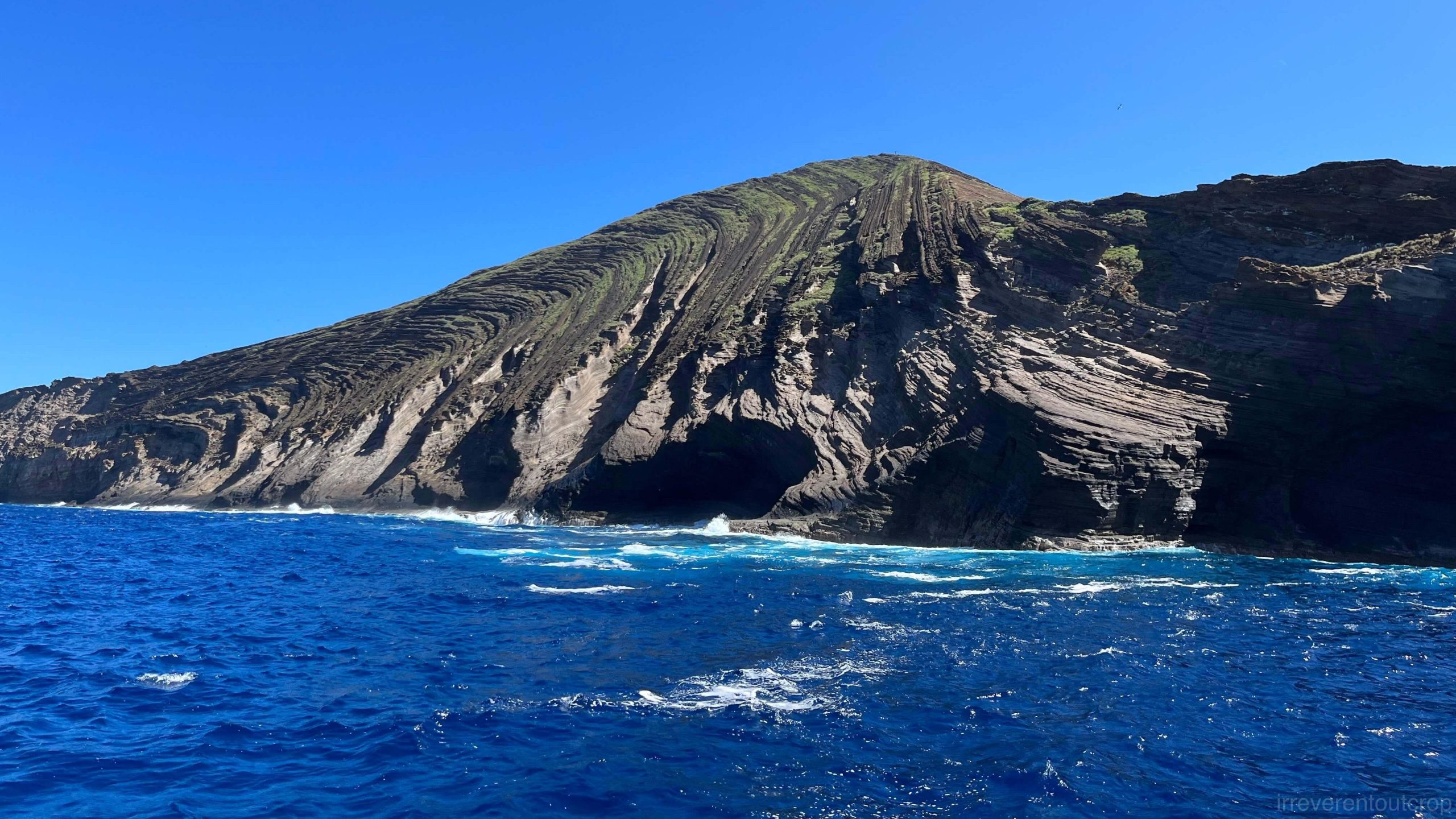

Lehua: the tuff cone

After marveling at Nā Pali’s dramatic cliffs, we sailed westward into the Kaulakahi Channel, where Niʻihau and its northern neighbor, the small tuff cone Lehua Island, came into view.

Lehua, a secondary tuff crater of Niʻihau’s ancient volcanic system, lies just 1.1 km / 0.7 mi north of Niʻihau. It has been built by explosive phreatomagmatic eruptions in which the proportion of gaseous to liquid matter is great [1]. Prevailing northeasterly trade winds deposited the thickest ash layers on Lehua’s leeward (southwestern) side, with particle size decreasing farther from the vent. Over time, compaction and cementation transformed these ash deposits into tuff—a pyroclastic rock bridging igneous and sedimentary origins, as it forms through volcanic eruption but consolidates via sedimentary processes.

Approaching Lehua from the southeast, we navigated into the narrow strait between the two islands.

Seabirds—mostly boobies and noddies—greeted us at Lehua’s southern edge.

Out boat anchored near the cliffs of Lehua’s SW corner. We then had some time to snorkel and have lunch. The sea water is crystal clear here and we can see Lehua’s near-vertical submarine drop-offs.

The tuff formations revealed distinct horizontal beddings, categorized by Harold S. Palmer (Geology of Lehua and Kaula Islands) into three layers: the main “summit tuff”, younger “post-summit tuff”, and older “pre-summit tuff” at the southern edge.

After lunch, we continued our tour and reached Lehua’s western side, where tuff beds twisted into dramatic anticlines. The cause—whether underlying bedrock irregularities or compression from volcanic debris—remained a topic of my curiosity. At the Neon Caverns, a gap in the cliffs hinted at pristine coral reefs below.

Next, we arrived at the northwestern tip of Lehua Island (the “West Horn”), where we saw a natural bridge commonly known as the “Keyhole.” The Keyhole is the result of wave erosion. The upper layer consists of newer post-summit tuff, which is harder and thus more resistant to erosion, while the lower layer, the summit tuff, has been eroded to form a hole.

The top of the hole marks the unconformity between the two types of tuff.

Turning to the sun-facing side of the West Horn, we reached the inner side of the crescent-shaped crater. The unconformity between the summit tuff and the newer post-summit tuff is quite obvious from here.

The inner side of the crescent-shaped crater is also made up of sea cliffs. I barely saw any bird nests here.

As our boat moved slightly farther away, we were able to see the entire West Horn of the tuff cone from the inner side of the crescent, including the “Keyhole”. It truly was a remarkable view!

Ni‘ihau: the “Forbidden Island”

With the weather being calm and clear, the captain decided to continue south along the eastern coastline of Niʻihau after circling around Lehua Island. We were able to have quite a great of those sea cliffs on the eastern side of Niʻihau.

Niʻihau Island is 30 km (18 mi) long and 10 km (6 mi) wide. The central and eastern parts of the island feature towering basalt plateau, which is the remnant of an ancient shield volcano’s northwest rim, while much of the flat land at both the northern and southern ends of the island consists of complexly mixed sedimentary rocks—ranging from biologically deposited white sandy beaches, alluvial fans formed by flowing water, to tuff deposits from volcanic ash.

According to the 2020 census, only 84 people live on Niʻihau. The village of Puuwai on the western side of the island is the only settlement. They are all Native Hawaiians, speaking the Niʻihau dialect of Hawaiian.

Niʻihau Island has a rather strange history: it is the only island in the Hawaiian archipelago fully controlled by a private family (the Scottish Robinson family). Since being “purchased” in 1864, the island has remained off-limits to tourists. The native residents of the island have preserved an almost isolated traditional Hawaiian way of life, making it an extreme example of cultural preservation in the face of globalization. However, since many of the younger generation now attend school on Kauaʻi, they are exposed to a more modern, convenient, and diverse lifestyle, and few return to settle on Niʻihau afterward.

Another event that made Niʻihau famous occurred during World War II, when a Japanese pilot, Shigenori Nishikaichi, crash-landed on the island following the Pearl Harbor attack. This incident sparked the widely publicized “Niʻihau Incident” across the United States.

Reaching the southernmost tip of the cliff, Pueo Point, our boat turned around, preparing to leave Niʻihau Island. Taking one last look back at Niʻihau, we could still see Kawaihoa Point, the southernmost point of the island, on the horizon.

On the way back, we could see Kauaʻi from a distance—indeed, it still resembled the classic shape of a shield volcano.

The end

The trip to the Nā Pali Coast, Lehua Island, and Niʻihau has come to a perfect end!

In addition to the sights, the local fruits on Kauaʻi are highly recommended too: sour sop, egg fruit, chocolate persimmon, banana, papaya, pineapple, and more— all are incredibly sweet and delicious. However, the local-grown ones aren’t available in large chain supermarkets and can only be found at street vendors or farmers’ markets.

Reference

[1] Geology of Lehua and Kaula Islands (by Harold S. Palmer)

[2] Geology of the State of Hawaii (2nd Edition, by Harold T. Stearns)