I took a trip to Micronesia – a group of isolated “small islands” – in early 2024, where the diverse volcanic landscapes on their high islands not only shape magnificent natural scenery but also foster an impressive local culture.

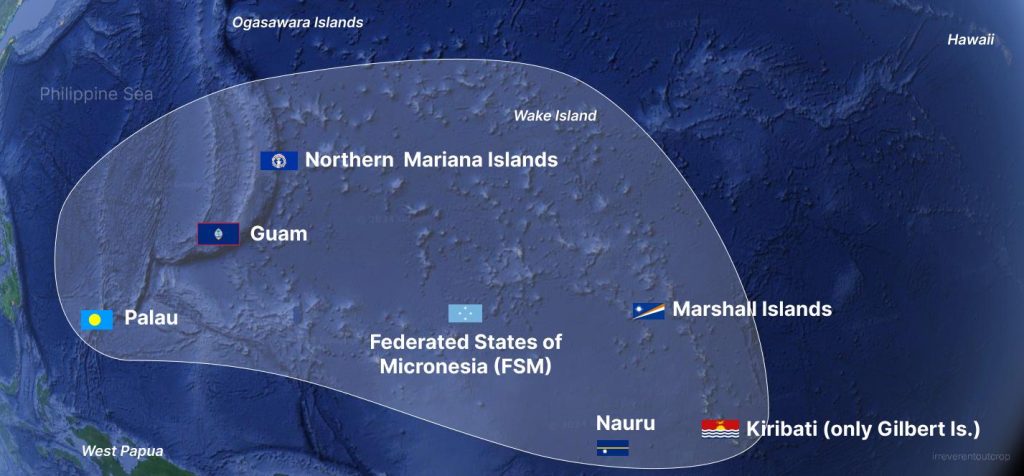

There are three subregions- both geographical and cultural- in Oceania: Melanesia, Polynesia, and Micronesia. Translated from Greek, they etymologically mean “black islands,” “many islands,” and “small islands“. The main distinction of Micronesia from the other two is the absence of continental islands (hence “small islands”…); the languages spoken by the islanders are all from the Austronesian language family but belong to different language groups; due to its proximity to Asia, Micronesia has been more influenced by Asian culture. The island group consists of over two thousand islands, spanning an astonishing 5,000 km / 3,000 miles east to west, which is way farther than the distance between Los Angeles to NYC, yet the total land area adds up to only 2700 sqkm / 1000 sqmi—smaller than the state of Rhode Island.

Note: Micronesia is a subregion name, and the Federated States of Micronesia (aka FSM) is one of the independent countries within this subregion.

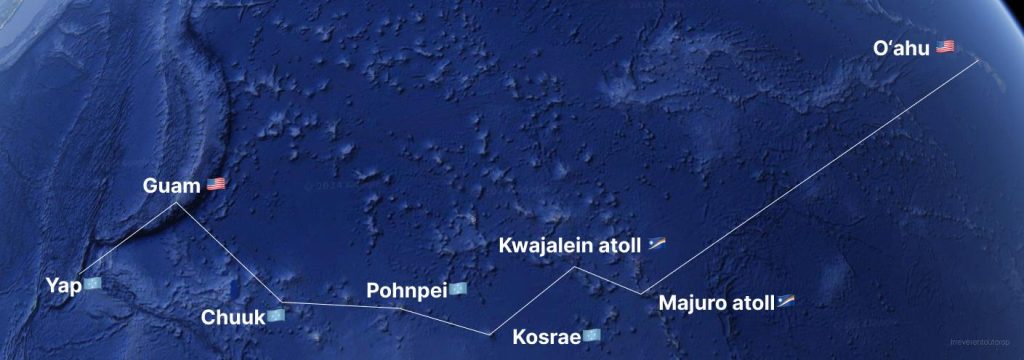

“High islands,” as the name suggests, are typically higher in elevation, mostly volcanic with fertile soil. In contrast, “low islands” are often coral atolls, characterized by poor soil and lacking surface runoff, making their living conditions harsher compared to high islands. In Micronesia, Kosrae, Pohnpei, Guam, and Yap are all high islands.

Pohnpei

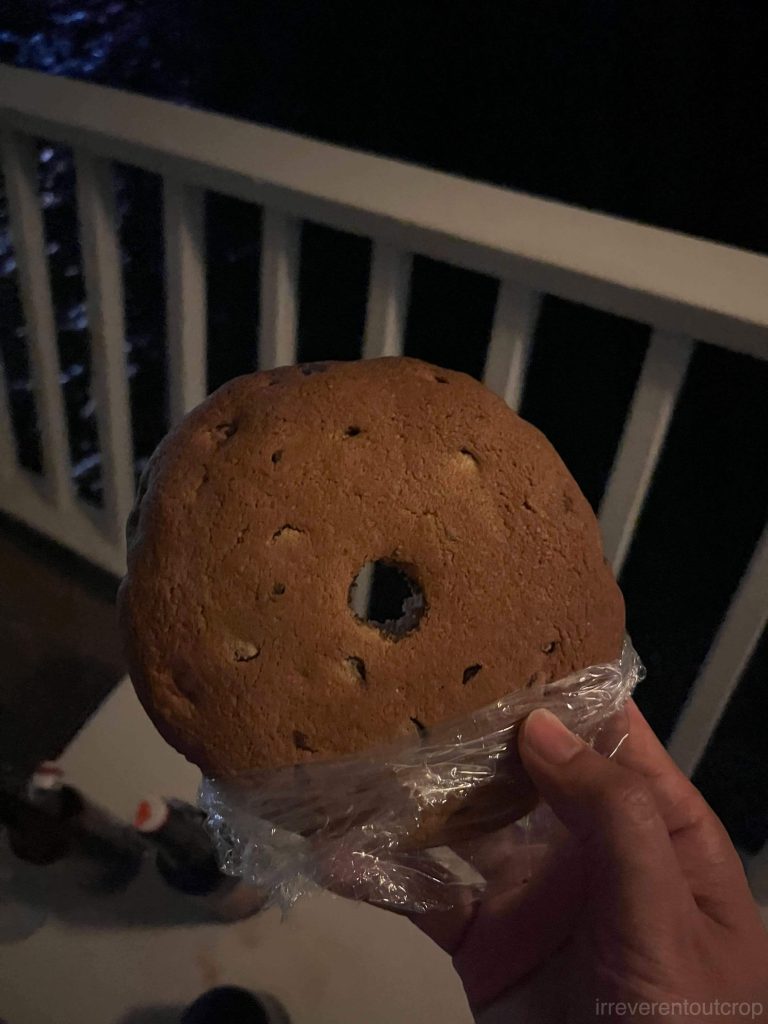

The highlight of this trip was undoubtedly Pohnpei Island – home to the Nan Madol ruins. The island spans an area of 334km2/ 130mi2, about 3 times bigger than the city of San Francisco. It’s entirely mountainous with rugged terrain and modest infrastructure. Pohnpei’s tropical climate and the highest peak in all of Micronesia at 782m / 2,565ft results in abundant rainfall and numerous waterfalls and streams. The island is rich in local produces — breadfruit, taro, bananas, coconuts, freshwater eels, sea cucumbers, various fish species, and more. Our local guide half-jokingly remarked, “If you get lost in the mountains, you won’t starve to death because everything you pick is edible.”

Speaking of Pohnpei’s local produce, one cannot overlook kava (known as “sakau” to Pohnpeians, and “kava” in Fiji)—a non-alcoholic traditional beverage made from the roots of the kava pepper plant. It has a numbing sensation and is known to promote relaxation. Though I approached it cautiously on my first try, the numbing effect was undeniable. This plant doesn’t grow outside the South Pacific islands, making it challenging to experience freshly prepared kava elsewhere.

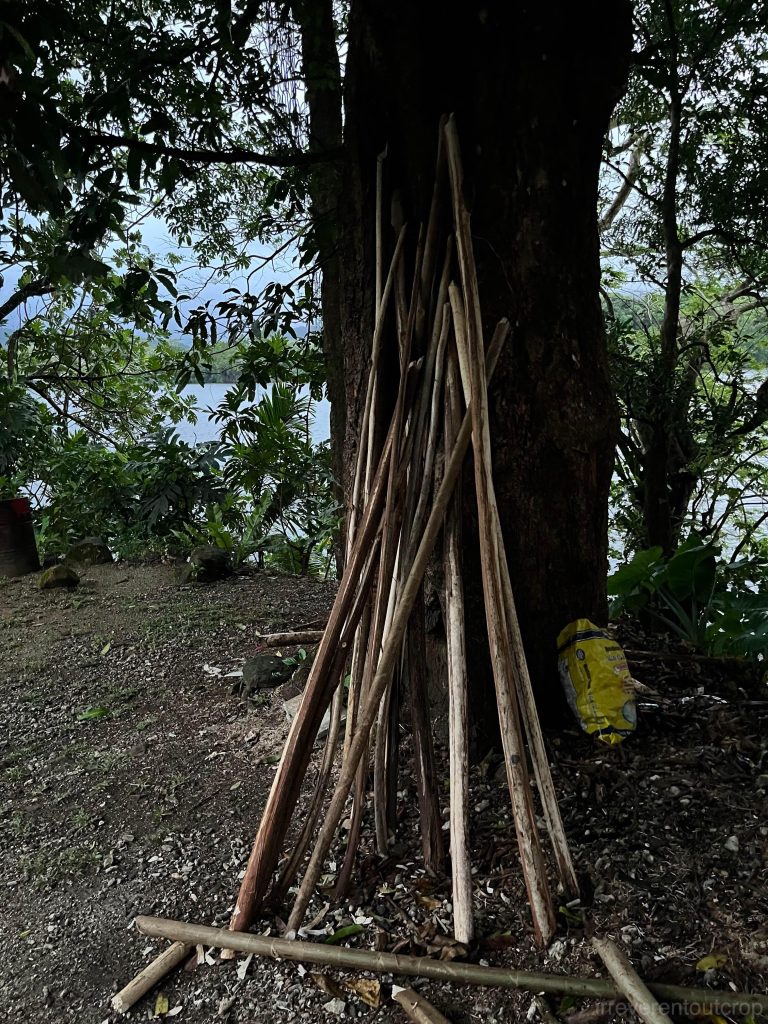

As for betel nut – almost everyone in Micronesia chews betel nut, much like in Papua New Guinea and Melanesia. Along the roadsides of Pohnpei Island, small shops display bundles of betel nut for sale. In the southern part of Yap Island, we saw locals using long poles to harvest betel nuts from tall betel nut palm trees in their backyards. The sidewalks often bear various shades of people’s spit marks as well.

Flying over Pohnpei, we could see the island’s rugged mountains and surrounding reef structures from the air. Right before we landed, we caught sight of the spectacular Sokehs Rock. Its basalt cliffs on the east, north, and west sides slope steeply down to the sea, making it prominent from land, sea, and air.

Japanese invaders built their artillery positions on this basalt outcrop during World War II, we climbed up there before leaving Pohnpei to pay a visit. After the Japanese military retreated, the local people of Micronesia lacked the resources and energy to clear the area, so the weapons remained preserved to this day, blending in with the surrounding vegetation.

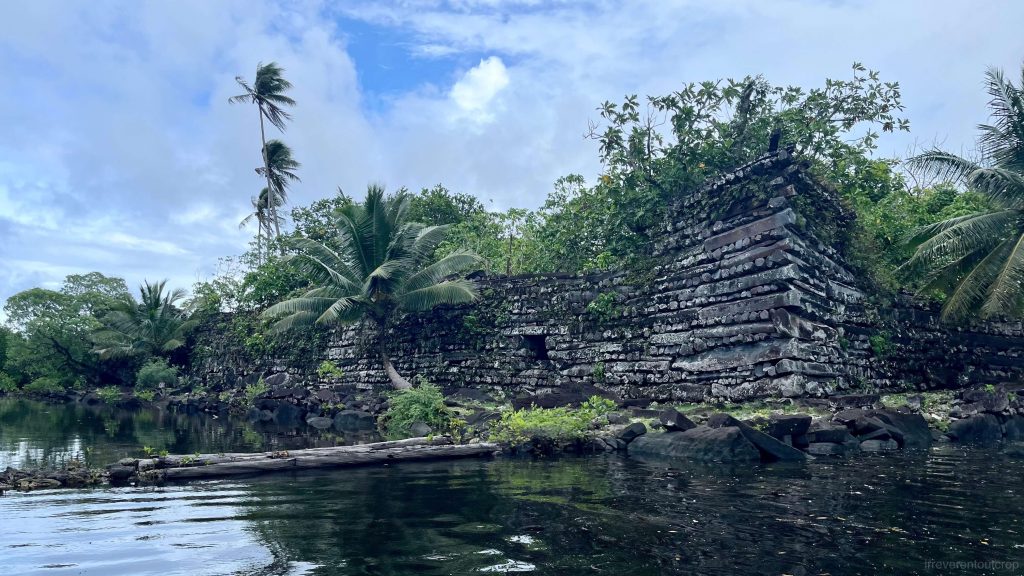

The entire Nan Madol site is constructed from basalt on the island.

Nan Madol consists of several hundred artificial islands interconnected by canals, serving various functions such as residential areas, meeting places, trading centers, religious sites, and tombs. I first learned about this place as a child from a book showcasing world wonders. It must has been over 25 years since I first read it.

We rented a small boat during high tide to visit Nan Madol so that we can not only see the main part of Nan Madol – known as Nan Dowas – but also to circle around the outer walls to view the other sections. During low tide, you can walk directly onto Nan Dowas, but the other parts would be too shallow for boats to navigate. Setting off from the dock, we navigated past reefs and quickly entered the canals within Nan Madol’s boundaries. Soon, the outer walls of central Nan Dowas came into view.

Upon reaching the staircase at the opening in the outer wall, our guide secured the boat, allowing us to ascend the steps. The staircase and pathways were remarkably well-preserved, likely the same way people entered from the open sea in ancient times.

Nan Dowas is believed to have served as a royal tomb site, but there are no artifacts remaining there to confirm this anymore.

Nan Madol is situated on the tidal flats at the southeast corner of the Pohnpei island, but the basalt columns used in its construction were proven to be sourced from the west side of the island. Each column could weigh between 20 to 40 tons, with some of the massive foundation boulders reaching 80 to 90 tons. The tallest remaining structure at the site is the outer wall of Nan Dowas, standing approximately 8-9m / 25-30ft high.

A foreign-origin dynasty called the Saudeleur emerged around 1000 years ago. Soon after their arrival, they built Nan Madol as their religious center and seat of government. They adopted a complicated social hierarchy and politics with clear residential separation between the nobility and the commoners. As for how craftsmen on this isolated island managed to cut huge basalt columns so precisely, transport them across the island to stack them into high walls on the tidal flats 800-1000 years ago, we can only speculate. Similarly, why they chose to construct in the tidal zone without which lacks freshwater and stable foundations, how their urban zones operated, and what are the details of social life—all these questions remain unanswered, as no historical records have provided definitive answers.

Their highly centralized rule eventually collapsed around the 16th century due to social upheaval by the locals and potentially environmental changes. After the downfall, Nan Madol was regarded as a place of taboo and has been gradually abandoned ever since. Most inhabitants of Pohnpei Island nowadays show no interest in visiting or protecting Nan Madol—they neither actively maintain nor deliberately destroy the site, allowing the structures to decay naturally on the tidal flats. This has created a weird situation that Nan Madol, once a prominent capital and now a UNESCO World Heritage Site known for its unique architectural style and rich historical significance, receives few visitors. The main threat to the preservation of the site comes from the roots of mangrove trees growing on its walls and the rising sea level caused by climate change, rather than direct human destruction or over-tourism.

Shortly after the tide began to ebb, we had to leave Nan Dowas to ensure we could still navigate our boat out in time. The outer periphery of the entire artificial island settlement was intricately arranged. Due to the dense mangroves, it’s nearly impossible to discern any coherent structure from a satellite map, but the unmistakable traces of human construction are quite evident up close.

It’s quite interesting how advanced our technology has become today—venturing into space, developing AI etc, and yet, standing before us is this large-scale ancient civilization site hidden deep in the ocean, about which we know so little. It evokes a sense of marvel tinged with irony.

Kosrae

Kosrae Island is located approximately 500 km southeast of Pohnpei Island. The Lelu Ruins on Kosrae share many similarities with Nan Madol on Pohnpei—they are both constructed from basalt boulders and situated in the tidal zone, although Lelu is slightly smaller in scale compared to Nan Madol. Visiting Lelu does not require a boat or guide – we literally just walked behind the store where we bought some bananas, then saw a sign indicating the Lelu Ruins. That’s it.

There are no fences, no entrance fees, no graffiti damage, and no other tourists. There’s an elementary school behind the Lelu ruins, so the ancient stone paths within the site are still used daily by local kids.

Some pathways may be submerged during high tide, altering the landscape and providing a different view.

There are several ancient marks where people pounded kava roots near the entrance, and further inside, there are numerous tombs. The large tree roots on the high walls look quite imposing—I wonder how long these stone walls can endure.

Kosrae Island has a another lesser-known site called Menka Ruins. Menka is located in the Yela-Ka forest and is estimated to be around 1,200 years old. Its purpose is currently believed to have been residential and a gathering place. The architectural style of Menka Ruins is notably different from Nan Madol and Lelu, as the stones seem to be more pillow basalt rather than column basalt.

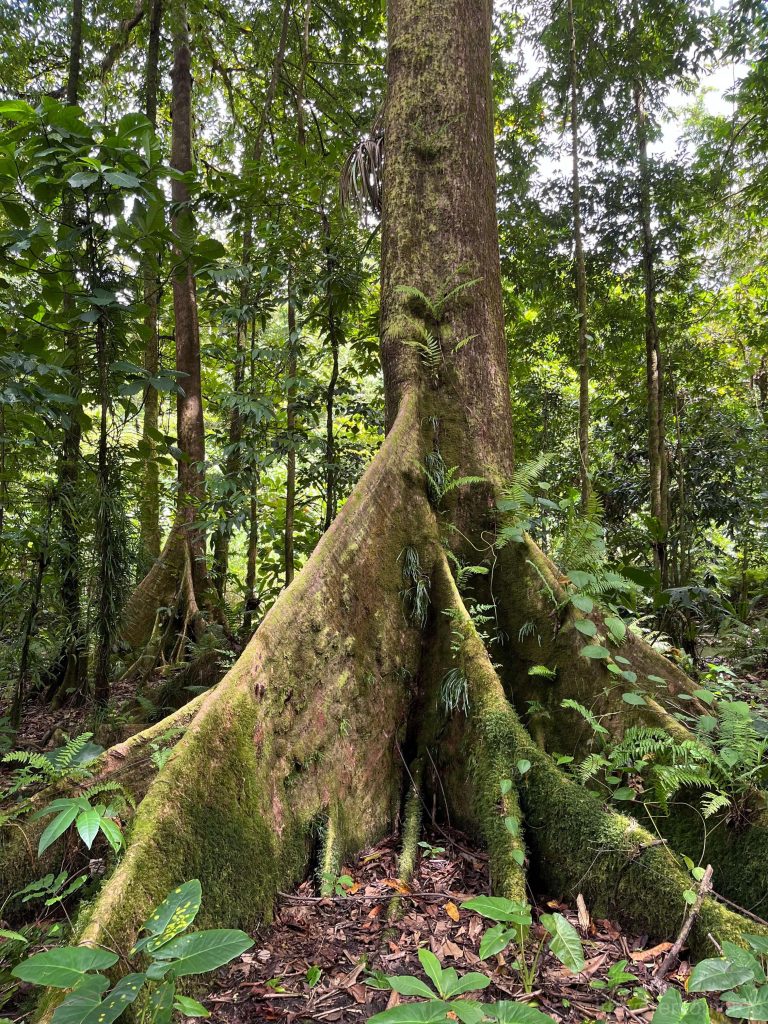

On the way to Menka, our guide also showed us the extremely rare “ka tree”. Found only on Kosrae Island and Pohnpei Island of Micronesia- more typical on Kosrae – ka trees are tall with well-developed buttress roots, making them extraordinarily striking and impressive.

Kosrae Island’s lush vegetation akin to a paradise owes much to its equatorial rainforest climate and the elevation of its mountainous terrain. It receives an average annual rainfall of 5000 mm (for comparison, Miami averages about 1500 mm annually; however, it’s still far less than crazy places like Cherrapunji, which receives over 20,000 mm annually due to its proximity to the Himalayas and frequent visits of monsoons). It rained every afternoon during our stay. However, after the rain, the weather during sunset time would clear up beautifully. From the eastern side of the island, the mountain known locally as “Sleeping Beauty,” with its clear foreground of serene lakes, looked exceptionally stunning after a rain shower.

The island has a population of 6,000 people, all of whom are locals. Their language is distinct from all other islands in Micronesia, but fortunately, there are schools where the native language is taught, ensuring its development is stable despite being different from others. Their diet is simpler compared to Pohnpei Island, with local produce like tuna, bananas, and coconuts, while other items are mostly imported.

Due to time constraints, our trip couldn’t include an overnight stay in Chuuk; we only had a brief look around near the airport after landing and caught glimpses of Chuuk Lagoon, which ranks the top ten largest lagoons in the world.

Guam

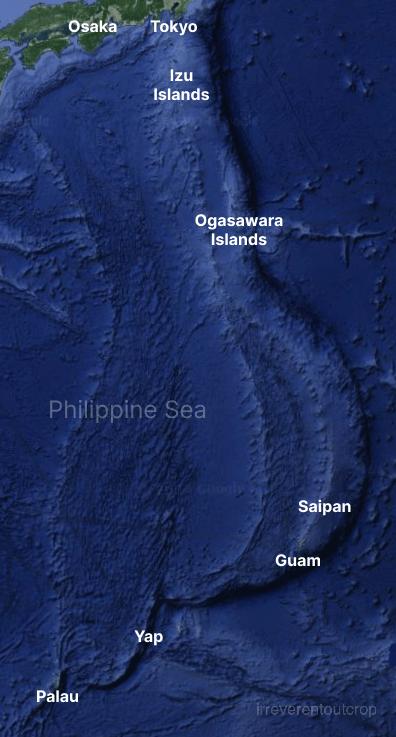

Starting from crossing the Mariana Trench and entering Guam, we left the Pacific tectonic plate and entered the scope of the Philippine tectonic plate. The compression between these two plates has created a continuous trench system (including the Mariana Trench) and a series of island arcs from north to south: starting from Japan’s Izu and Ogasawara Islands, extending south to Saipan and Guam, then turning southwest to Yap and Palau. Islands like Kosrae, Pohnpei, and Chuuk, which are not on the plate margins, are generally believed to be formed by “magma hotspots,” distinct from the plate compression that affects islands like Guam and Yap. Geographically, Guam and Yap also have fewer prominent peaks compared to Kosrae and others volcanic islands, and have a drier climate and relatively lower precipitation.

Guam is a U.S. territory, and its tourism primarily targets Japanese and Korean tourists, as well as U.S. military personnel. Tumon Bay Beach is quite nice, but don’t expect too much from shopping and dining. Spain colonized Guam from the 16th century, and it fell under U.S. Army’s control in 1898, which has persisted to this day. The indigenous CHamoru (sometime written as “Chamorro” as well) culture has thus been largely erased, unfortunately.

The CHamoru (“ch” is treated as a single letter in their language, so both “c” and “h” are capitalized when written in uppercase) language belongs to an independent branch within the Austronesian language family, and the CHamoru are the only Micronesian culture to have developed pottery. Among their scarce cultural heritage still left, the most representative are the latte stones—traditional CHamoru house supports. Near the Spanish Plaza in the capital of Hagåtña, Guam, there is a small park dedicated to eight ancient latte stones.

The symbol of latte stones is often seen all over Guam.

Yap

Yap Island (locally known as Wa’ab rather than Yap) is not part of United Airlines UA154’s island-hopping flight route. If you want to go there, you’ll need to fly specifically from Guam (another less common way to get to Yap Island is to take a small church plane from Palau). There are two flights from Guam per week, both late at night. Personally I wonder if anyone has ever seen what Yap Airport looks like during the day LMAO.

Yap Island’s underwater sceneries are spectacular, which I’ll detail in another post. For now I’d love to talk more about Yap Island’s stone money (or “rai”; some also call it “disk money”) and local customs, which operates like a unique tripartite chieftaincy system supported by original blockchain-like technology, a singular phenomenon in the world and a living history of human civilization. Fortunately, it escaped the ravages and devastation of western colonizer powers during the colonial period, allowing its traditional culture and social structure to endure.

It is mentioned online that there are seven caste layers on the island, but we couldn’t really confirm the exact accuracy of the numbers during the visit. However, historically, there has indeed been a stratification among villages on the main island. Alliances between these communities were intricate and often involved three factions, serving to balance power dynamics.

The local economy is highly closed-off. Even though contemporary daily transactions now use the US dollar, traditional stone money still circulates and holds irreplaceable value in major transactions such as real estate, land, and large celebrations or weddings. These stones were quarried centuries ago up until the early 20th century from limestone caves in Palau (400km / 250miles away), transported to Yap by small wooden canoes, and meticulously shaped and polished.

Originally used as currency, these stones gained value due to the difficulty of transportation from Palau and the laborious polishing process, rather than their size or color.

Yapese language does not have a writing system. Information about the over 6,000 stone money pieces- such as their value, ownership, and transaction history- is preserved through oral history and recited poetry by the whole community. An economic “incident” happened when an Irish-American guy named David O’Keefe got to Yap in the late 19th century- he used modern techniques from Hong Kong to cut some stones and transported them to Yap, introducing a wave of inflation. Consequently, the locals decided to cease the production of new stone money. Because existing stone money remains tradable even if lost (such as sinking to the sea floor), the total value of all stone money has remained constant since then.

Initially serving as currency, Palau’s stones were suitable because Yap itself is mostly igneous or metamorphic rocks and lacks sedimentary rocks like limestone. Yapese ancestors travelled 400km of open water and found limestone in Palau, thought it’s really rare, then began quarrying and transporting them back home in pieces. The small ones are about the size of half of a palm, while the large ones can be taller than a person and weigh 3-4 tons.

Because of its shared oral ledger, public and transparent verification of transactions, and the scarcity of rai production, some people refer to this system as world’s oldest blockchain technology.

Many villages have stone money banks where these stones are openly displayed in rows. Because the information about stone money is recorded in oral poetry, nobody would attempt to move or steal these stones.

On our second day in Yap, we asked our hotel front desk if he’s able to guide us for a tour to the largest stone money bank of Yap, in a village called Mangyol. It’s very nice of him that he agreed. Mangyol is located on the north side of the island, and we wouldn’t have been able to get in without a local guiding us because it’s in a private village.

According to researches, the stone money bank of Mangyol has 72 stone money pieces. Some are stored overlapping, which is super rare in Yap. “People from this village love showing off their fortune, don’t they” joked by our guide.

Yapese people are thriving quietly on a remote Island without the need for expansion, and supporting themselves with a self-sufficient agricultural economy without worrying about financial crisis. It reminds me of a Taoism quote from Laozi’s Tao Te Ching:

“Let it be a small country, with a small population. Let the supply of goods be so plentiful that it counts in tens and hundreds, but teach the people to choose not to use them. Teach the people not to risk death lightly and not to migrate far. Although there are boats and carriages, none will choose to rid in them. Although there are armour and weapons, there will be no need to display them.”

Many thanks for your insightful first-hand account of visiting so many of these lithic cultural sites across the Western Pacific. It’s quite helpful to read your impressions.

Such an exotic and fascinating part of the world so few get to see and you brought it alive. I now have a reason to stare at that part of world with more curiosity and wonder. Thank you so much for sharing your experience and insight into the culture, history and geography. I learned so much…great stuff! I l can’t wait to see more. 🥰