Last autumn, we explored the vibrant foliage of Hokkaido’s Shikotsu-Toya National Park (支笏洞爺国立公園), visiting Lake Toya, Noboribetsu Hell Valley, and Lake Shikotsu—all iconic natural landmarks. A must-see for nature enthusiasts!

Geology overview of Hokkaido

Hokkaido has a complex geological structure, with numerous faults, volcanoes, and geothermal features across the island. It sits on the Okhotsk Plate1, which is compressed by the Eurasian Plate on the west and subducted by the Pacific Plate on the east. The north-south Hidaka Mountains in central Hokkaido are formed by a thrust fault and are generally considered the boundary between the Kuril Island Arc and the Northeastern Japan Arc.

Several volcanoes and geothermal areas are concentrated in the central Hokkaido region, including Lake Toya, Lake Shikotsu, Noboribetsu Hell Valley, Mount Yotei, and Jozankei. Together, they form Shikotsu-Toya National Park. The Toya Caldera and Mount Usu have even been recognized by UNESCO as a Global Geopark.

We traveled in a ”counterclockwise“ loop:

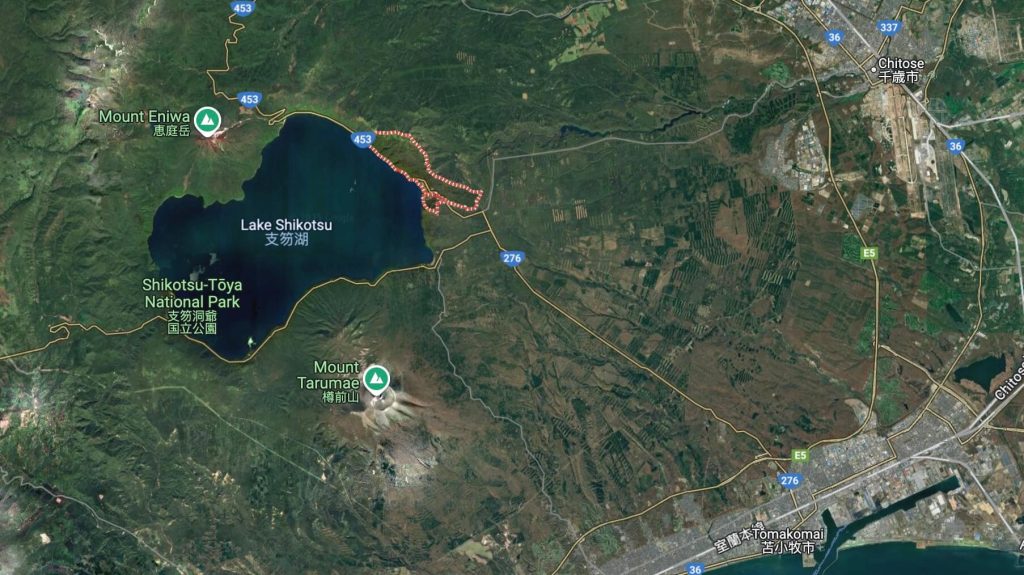

- Arrival in Sapporo: ✈️ We landed at New Chitose Airport and took a train 🚄 north into Sapporo. The airport is actually located in Chitose, which lies east of Lake Shikotsu and south of Sapporo. There’s an interesting connection between the names “Shikotsu” and “Chitose”—I’ll explain more later when we get to the Lake Shikotsu section.

- Sapporo ➔ Lake Toya: We took the Donan Bus Company’s “Sapporo–Lake Toya Line” express bus 🚌, which goes directly to the Lake Toya hot spring area. Be sure to reserve seats online in advance.

- Lake Toya ➔ Noboribetsu Hell Valley: Our onsen hotel provided a free shuttle to JR Toya Station, then we took a JR train 🚄 to Noboribetsu Station and grabbed a taxi 🚕 for a 10-minute ride up into the valley.

- Noboribetsu Hell Valley ➔ Lake Shikotsu hot spring area: From the valley, we took a bus 🚌 back to Noboribetsu Station, then a JR train 🚄 to Tomakomai Station, and finally a taxi 🚕 to Lake Shikotsu.

- Lake Shikotsu ➔ New Chitose Airport: A local bus 🚌 runs directly from Lake Shikotsu to the airport.

Driving would’ve definitely saved us some time, but traveling entirely by public transportation was honestly a fun part of the experience as well!

Sapporo 札幌

If you’re visiting Sapporo like us in autumn to see the foliage, Nakajima Park, the Hokkaido University campus, and Mt. Maruyama are all great spots. The scenery at Nakajima Park and Hokkaido University is more landscaped and planned, while Mt. Maruyama features a patch of native temperate broadleaf mixed forest that has never been logged or disturbed—a rare sight to see preserved so well.

Otaru has some nice spots with great foliage in the mountains as well, but since we were there for just a day trip, we only explored the central canal area and didn’t make it up the mountains to see the leaves there.

Many people might not know this, but the names “Sapporo” and “Otaru” both come from the Ainu language, the language of the indigenous people of Hokkaido. “Sapporo” originally means “a wide, dry river“, while “Otaru” means “a river in the sand“.

Ainu is considered a “language isolate” from linguistics perspective, not related to any other language family. Historically, it was spoken in Hokkaido, the Kuril Islands, and the southern part of Sakhalin Island, but now the dialects from the Kurils and Sakhalin have completely disappeared. Only a few elderly people in Hokkaido still speak the Hokkaido dialect, making it an extremely endangered language. It’s not until 2008 that the Japanese government officially recognized Ainu as the language of its indigenous people, and the following year, it began planning some language preservation programs.

Lake Toya 洞爺湖

The express bus from Sapporo to Lake Toya Onsen took about two hours. We passed by the base of Mount Yotei along the way. The Niseko area on the western side of Mount Yotei is a popular ski resort, but for someone like me who isn’t too fond of winter sports, I’d skip that part for now.

The name “Toya” in Ainu means “land by the lake shore“. About 110,000 years ago, a massive volcanic eruption caused a collapse, forming a caldera that eventually filled with water to become Lake Toya. At its center, a lava dome called “Nakajima” rises above the water. When viewed northward from the southern shore, the lake’s deep blue waters contrast sharply with the backdrop of Mount Yotei, creating a stunning view.

There would be fireworks over the lake every evening from late April to the end of October. We happened to catch the final week of this “fireworks marathon”!

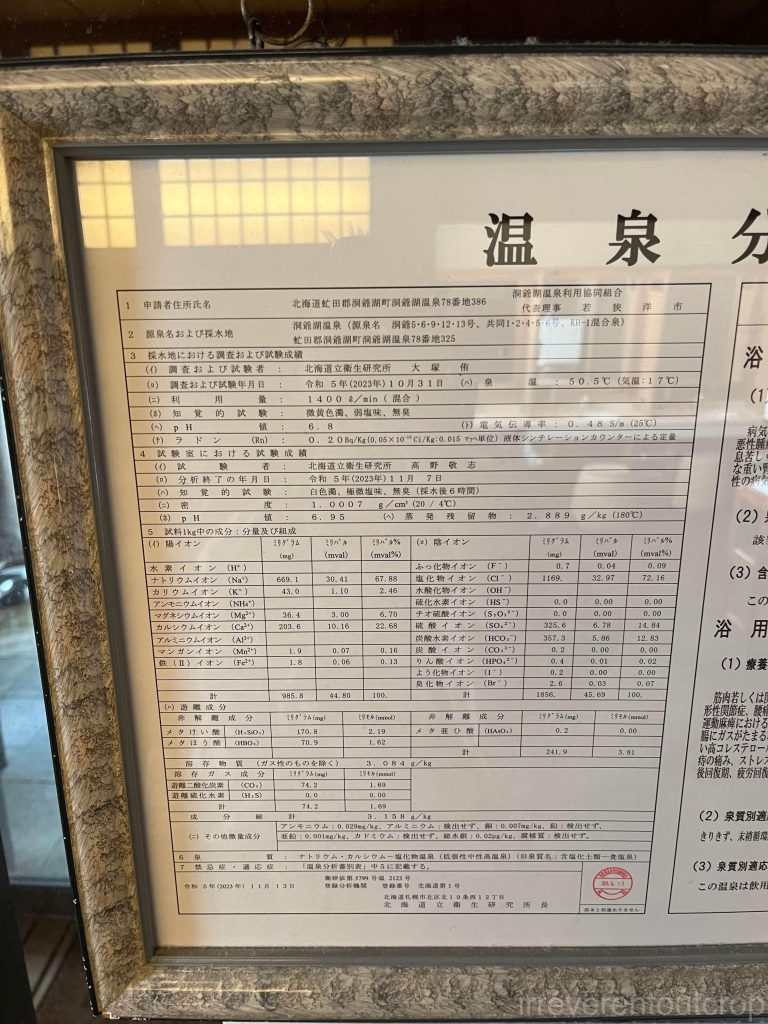

Our onsen hotel is located on the southern shore of the lake. The onsen here is carbonated hot spring, which makes the skin feel smooth and leaves no sulfur smell. The hotel lobby also offered unlimited shochu to taste.

We took the bus to Mount Usu and Showa Shinzan on the second day at Lake Toya. Mount Usu is an active stratovolcano, while Showa Shinzan is a secondary lava dome located on the eastern slope of Mount Usu. The bus stop is conveniently located between the two mountains, and after getting off, we could just take the cable car directly to a viewpoint at the summit of Mount Usu. From there, people can look back at Showa Shinzan, overlook the alluvial plain of Nagawa River, or get a close-up view of the crater of Mount Usu.

Usu means “small bay/river mouth” in Ainu. I’d think all the flowers and plants up here probably have their original Ainu names as well, but it’s hard for us to verify them all.

There’s a trail along the southern rim of the crater of Mount Usu, offering great views all along the way, though the wind is really strong. The trail ends at the Minami-gairinzan Lookout, where we could see several of Mount Usu’s core craters in the sunlight, as well as Lake Toya in the distance and Mount Yotei on the horizon.

We were lucky to have clear weather, and the views while walking along the crater were fantastic. If it had been rainy, though, there’s no shelter here, so I imagine the experience would have been less enjoyable.

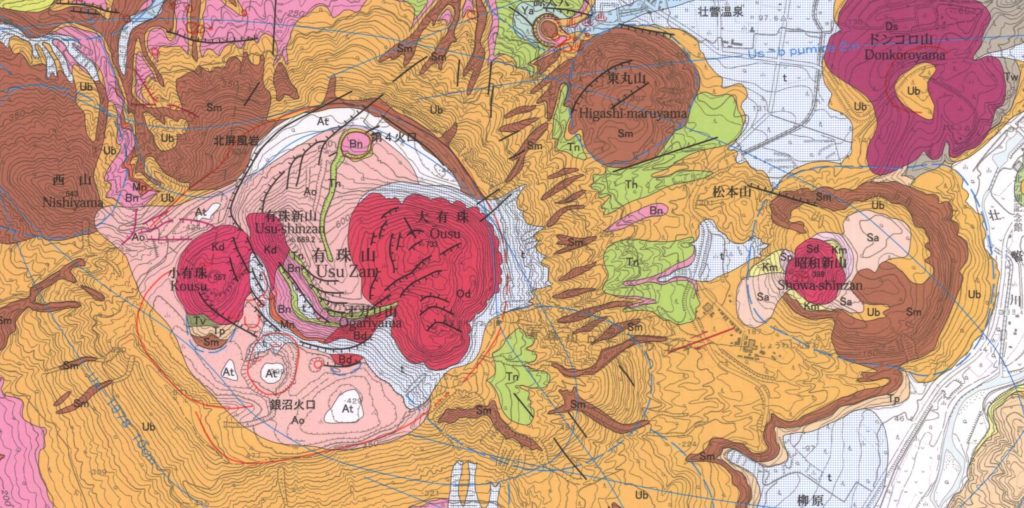

Mount Usu is primarily composed of dacite (a felsic extrusive rock rich in quartz, intermediate in composition between andesite and rhyolite), along with abundant pumice, volcanic ash, and other volcanic debris. In terms of eruption chronology, the main body of the Kousu formed in 1769 (the 5th year of the Meiwa era), the O-Usu formed in 1853 (the 6th year of the Kaei era), and Showa Shinzan erupted between 1943 and 1945 (the 18th to 20th years of the Showa era).

The “West Mountain” Nishiyama, however, is much older, having formed around 10,000 years ago, and is mainly composed of basalt, which is quite different from the dacite others.

As mentioned at the beginning of the article, the magma formation process in this area is closely related to the crust due to its location within a system of the island arc along a subduction zone. Unlike magma at mid-ocean ridges or hotspots, which originates directly from the mantle’s deeper layers, the magma in island arc systems is formed when oceanic crust subducts, carrying water-laden crust down. The presence of water lowers the melting point of the upper mantle, causing partial melting and the formation of magma. As the magma rises, it interacts with the crust again before erupting.

This type of magma has a higher % of silica, which is why the volcanic rocks formed here are mostly andesites and dacites (more felsic than basalt). Another blog post of mine about several shield volcanoes and basaltic landscapes I’ve visited could be an interesting reference for those interested to compare: Volcano (part 1): shield volcanoes.

After returning to the lakeside of Lake Toya, we walked to the western slope of Mount Usu to visit a disaster remain site. A brand new crater – Kinpira (金比羅) Crater – was created during that significant eruption in March 2000. The damaged buildings in the area have since been preserved as a historic site.

Noboribetsu Hell Valley 登别地獄谷

Our hot spring hotel offered us a free shuttle ride to Toyako JR train station when we left, and then we took the train, passed around the Etomo Peninsula, and eventually arrive at Noboribetsu. Train services are quite frequent along this line, and you can just buy tickets at the station on the day of travel during off-season.

Noboribetsu—such a unique name and located in Hokkaido—is, of course, also a name of Ainu origin, with the original meaning being “dark and murky river“.

Since we only planned for a day trip in Noboribetsu on the way to Lake Shikotsu, we dropped off our luggage at Noboribetsu Station and, to save time, took a 10-min taxi directly to Hell Valley (Jigokudani). Noboribetsu Hell Valley is also a famous hot spring area, and I’d guess it’s even more well-known than Lake Toya, as it felt much more crowded here. The main attraction area is divided into two parts: “Hell Valley” and “Oyunuma”, with the entrance leading straight to Hell Valley, and Oyunuma just up the hill.

The geothermal landscapes around Noboribetsu sit atop an ancient volcanic crater. Although the magma beneath the surface no longer erupts, it still heats underground water trapped in the saturated layers, causing geysers to spout and steam to rise through cracks and vents. There are also bubbling mud pools throughout the area. Vegetation can’t really grow near the geothermal vents due to the high sulfur content in the soil and rocks.

Following the trail uphill leads to Ōyunuma and Okunoyu. These two geothermal lakes have different sizes but both are steaming, bubbling with murky water, and filled with the sharp scent of fresh sulfur. The water is highly acidic (pH 1–2), and sulfur springs bubble up from vents that can reach temperatures around 130°C at the bottom of the ponds, .

The autumn scenery along the Ōyunuma River trail is absolutely delightful.

Just east of Jigokudani lies Lake Kuttara—a nearly perfect circular crater lake said to have exceptionally clear water. However, we couldn’t find an easy way to reach it from the valley. It was a bit too far to walk, and with limited time, we eventually had to give up on the idea.

Lake Shikotsu 支笏湖

Getting from Noboribetsu to Lake Shikotsu was one of the big uncertainties when we were planning the trip, since we weren’t sure how long we’d end up spending in Noboribetsu, whether we’d be able to find a taxi in Tomakomai, or if catching one of the limited-service shuttle buses to Shikotsu from Chitose Station would even be feasible…

Well, Noboribestu’s Hell Valley ended up to be well worth a thorough visit, so we stayed there until the afternoon. Wanting to catch the sunset at Lake Shikotsu, we decided to get off the train at Tomakomai and take our chances with finding a cab.

Tomakomai turned out to be quite a proper and highly industrialized town. Not particularly crowded, but with solid infrastructure, and sure enough there were taxis waiting right outside the train station, so we got one without any trouble!

The hotel staff mentioned that many people from Sapporo drive over on weekends since it’s not far at all if you drive.

The names “Tomakomai” and “Shikotsu” are quite unusual and, not surprisingly, have their origins in the Ainu language as well. “Tomakomai” originally means “river deep in the swamp“, while “Shikotsu” refers to a “huge basin“. However, since the pronunciation of “Shikotsu” in Japanese can also be understood as “dead bones” (死骨) which sounds too eerie, the name of the lake was kept, but the nearby town’s name was changed to “Chitose” when transliterated into Japanese, written as 千歳 — yes, the same name as the location of Sapporo’s airport.

Lake Shikotsu was formed in a similar way to Lake Toya, through the collapse of an ancient (40,000 years ago) volcanic crater, creating a crater lake. With a maximum depth of 360 meters, it is Japan’s second-deepest lake, only behind Lake Tazawa.

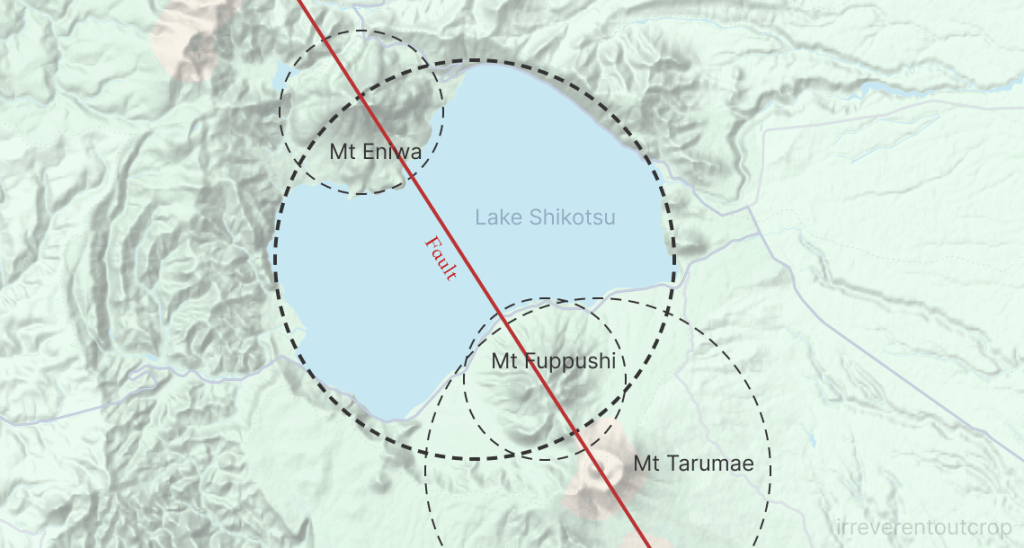

But why isn’t Lake Shikotsu round like Lake Toya?

To answer this, we need to consider the three volcanoes surrounding Lake Shikotsu: Mount Eniwa, Mount Fuppushi, and Mount Tarumae. After the eruption that formed this big crater, volcanic activity continued around the edges, leading to the formation of these three new stratovolcanoes. The mountains from these volcanoes partially filled the lake, causing the originally round shape of the lake to curve on both the northern and southern sides.

If we draw a line connecting the centers of these three volcanoes and the original center of the crater lake, we can see that they all align! This line marks the fault that shaped this chain of geological features.

The animation on this website explains it quite well: https://www.web-gis.jp/GM1000/SelfSelect/Self-Select_086.html . Feel free to check it out if you are interested.

As for the names, Eniwa in Ainu language originally means “sharp mountain“, Fuppushi means “place with cedar trees“, and Tarumae means “high ground by the river“. I find them all quite poetic yet very down-to-earth.

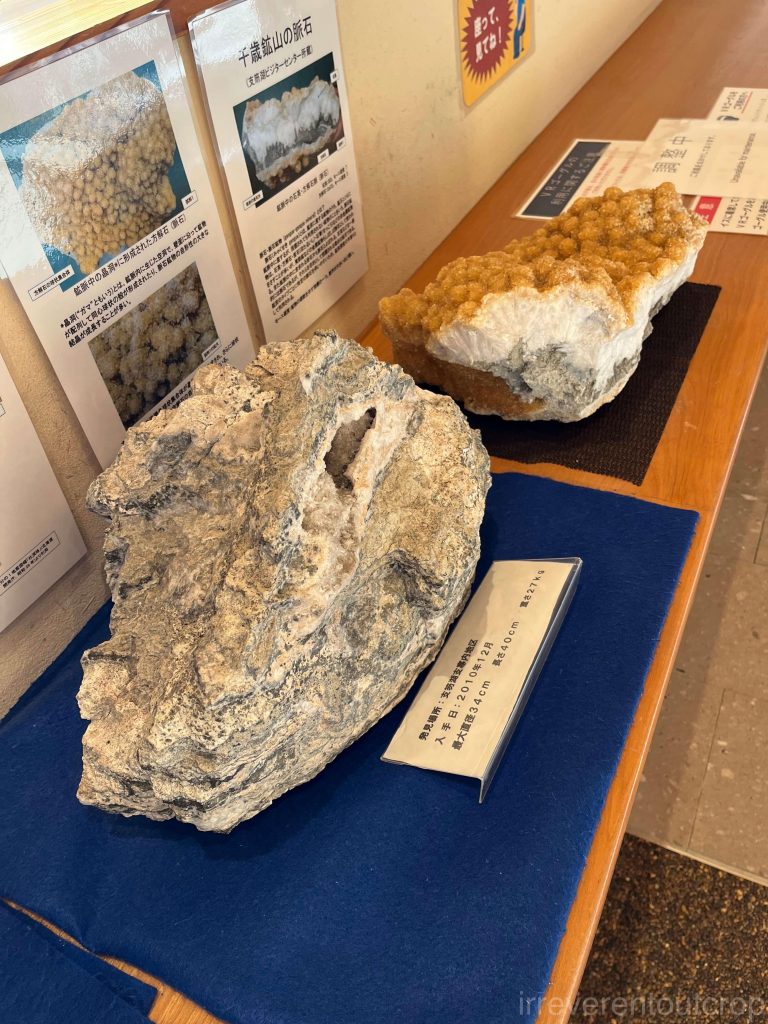

The core area of the Shikotsu Lake hot springs has a visitor center, which includes a detailed geological exhibition. It’s really well set up and I learned quite a lot from it.

Across from the hot springs, on the other side of the Chitose River, there is a small hill with beautiful red leaves.

On our last day at Lake Shikotsu, we rented bikes from the visitor center and biked along the road all the way to the foot of Mount Eniwa.

The rocky beach at the foot of Mount Eniwa is a public park. Many people were having picnics when we visited. The water looks specially clear in the soft sun lights.

Right: The warm afternoon sun shining on the hillside by the lake, covered with yellow leaves.

We slowly biked back as the sun was setting. When we reached halfway and looked back at Mount Eniwa, we saw the sun perfectly casting the mountain’s shadow from its base onto the clouds above, creating a truly unique sight.

Thoughts on food in Hokkaido and the local agriculture

Our food experience of this whole trip in Hokkaido was quite nice! Both Sapporo and Otaru have fish markets where the seafood is fresh, delicious, and reasonably priced. The local soup curry and miso ramen are also very distinctive, with rich, deep flavors and layers of taste.

Preserving local agricultural practices can lead to remarkable improvements in food quality—a rarity in many developed nations where industrialization often overshadows traditional farming. Hokkaido, with its subarctic climate, offers a compelling example. Rather than chasing exotic or delicate crops ill-suited to its environment, the region specializes in hardy staples: potatoes, radishes, corn, dairy, and other robust produce. This focus on climate-appropriate farming minimizes the need for long-haul transportation or industrial preservation methods. The result is fresher, inherently high-quality ingredients that require little embellishment. Without the compromises of extended supply chains, even simple dishes achieve a striking depth of flavor, embodying an authenticity that modern food systems frequently sacrifice.

The End

To conclude, as a mark of respect for the endangered Ainu language of Hokkaido’s indigenous people, let’s review the original meanings of the place names mentioned in this article one more time (the Ainu language words in parentheses are in katakana and the Ainu pronunciation):

- 札幌 Sapporo (サッ・ポロ・ペッ sat-poro-pet): Dry and wide river.

- 小樽 Otaru (オタ・オル・ナイ ota-or-nay): River in the sand.

- 洞爺 Toya (トー・ヤ to-ya): Land at the lakeshore.

- 有珠 Usu (ウㇲ us): Small bay.

- 登别 Noboribetsu (ヌプルペッ nupure-pet): Dark, murky river.

- 苫小牧 Tomakomai (ト・マㇰ・オマ・ナイ to-mak-oma-nay): River deep in the swamp.

- 支笏 Shikotsu (シ・コッ shi-kot): Huge hollow.

- 恵庭 Eniwa (エ・エン・イワ e-en-iwa): Sharp mountain.

- 風不死 Fuppushi (フプシ fupushi): Place with cedar trees.

- 樽前 Tarumae (タオロマイ taor-oma-i): High place by the riverbank.

Note:

- Some geological theories classify the Okhotsk Plate as part of the North American Plate.