We visited the Grand Canyon in Arizona this spring and hiked all the way to the bottom! Starting with the Kaibab Formation at the top, which formed around 270 million years ago during the Permian period, and moving down to the Vishnu Schist at the canyon floor, which formed 1.7 billion years ago during the Proterozoic Eon, we explored the entire geological timeline in reverse.

The day before we descended to the canyon floor, we entered through the east entrance of the South Rim of Grand Canyon National Park. Our first stop was the Desert View Watchtower, which offers some of the best views. It’s one of the few places at the rim where you can directly see the Colorado River at the canyon floor.

We stopped by several different viewpoints when driving west along the Desert View Drive on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. It was just in time for sunset when we reached Grand Canyon Village.

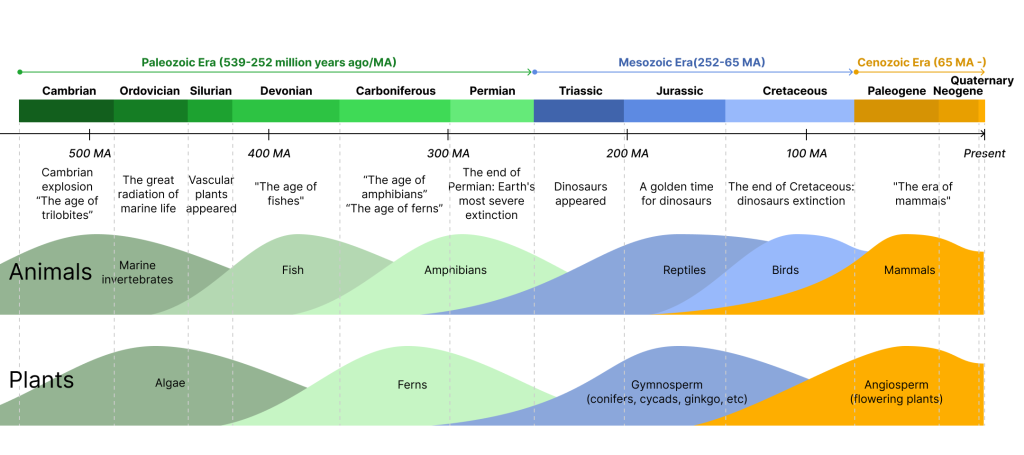

The Grand Canyon has a rich stratigraphy, with its geological sequence roughly divided into nine units/layers. Except for the bedrock at the bottom, which is schist (a type of metamorphic rock), the eight layers above consist of sedimentary rocks from different geological periods.

Arranged by their formation periods, the top four units were formed during the Permian period (300–250 million years ago), followed by two units from the Carboniferous period (360–300 million years ago) then some scattered rocks from the Devonian period (420–360 million years ago). Interestingly, no rocks from the Silurian period (440–420 million years ago) and Ordovician period (490–440 million years ago) could be found in the sequence. The deepest sedimentary rocks were formed during the Cambrian period (540–490 million years ago). The metamorphic bedrock from the Precambrian period dates back to 1.7 billion years ago.

The unconformity between the Cambrian sedimentary rocks and the bedrock spans 1.2 billion years and is known as the “Great Unconformity.”

The Mesozoic Era, often referred to as the ‘Era of Dinosaurs,’ began with the Triassic period. Since the youngest rocks in the Grand Canyon are from the Permian period, all the fossils of marine and terrestrial life here are from the Paleozoic Era and earlier, and do not include dinosaur fossils.

The formation of the Grand Canyon from a basin is primarily due to the Laramide Orogeny at the end of the Cretaceous period (the time of the dinosaur extinction), which caused the region’s layers to uplift. Afterward, processes such as river erosion intensified, resulting in the deep canyon we see today. Millions of years of erosion removed most of the Mesozoic sedimentary rocks, while the older Paleozoic rocks, protected by the hard Kaibab Formation (the top layer in the Grand Canyon today), remained visible.

Some formation units of the Grand Canyon are cliff-formers, while others are slope-formers. Softer, more erodible layers tend to form slopes, while harder rocks form cliffs. We will go through these in more detail later.

Permian formations

We woke up the next morning, packed some water and energy snacks, then started our descent into the canyon via the Bright Angel Trail.

If we had gotten up earlier in the morning, we would have had enough time to take the steeper South Kaibab Trail down to the canyon floor & Colorado River, and then return via the Bright Angel Trail, avoiding retracing the same route. However, since we were a bit pressed for time, we had to stick to the Bright Angel Trail both ways.

This area was a shallow sea during the Permian period, which allowed for the extensive formation of sedimentary rocks. Each of these four layers has its own distinct characteristics.

1. Kaibab Formation

The Kaibab Formation is the topmost layer of the Grand Canyon. It is a hard unit that has protected the strata beneath it, while the Mesozoic layers above have almost completely been eroded away. The Kaibab Formation is a typical cliff-former, primarily composed of limestone, with a mixture of dolomite, sandstone, and other sedimentary rocks. Its color is relatively light, and it is clearly visible on both the North and South Rims of the Grand Canyon. Many of the triangular mountain peaks that appear to have “caps” on top are actually composed of this layer.

2. Toroweap Formation

This unit has a highly mixed and complex composition, including sandstone, shale, limestone, and gypsum. It is generally softer and more vulnerable to erosion, making it the uppermost slope-former where soil can form and trees can grow. From a distance, it’s easy to recognize the sloped area covered in vegetation, situated between the steep cliffs of the Kaibab Formation at the top and the bright, thick white layer of the Coconino Sandstone below.

The slope of the hiking trail here also becomes much gentler.

3. Coconino Sandstone

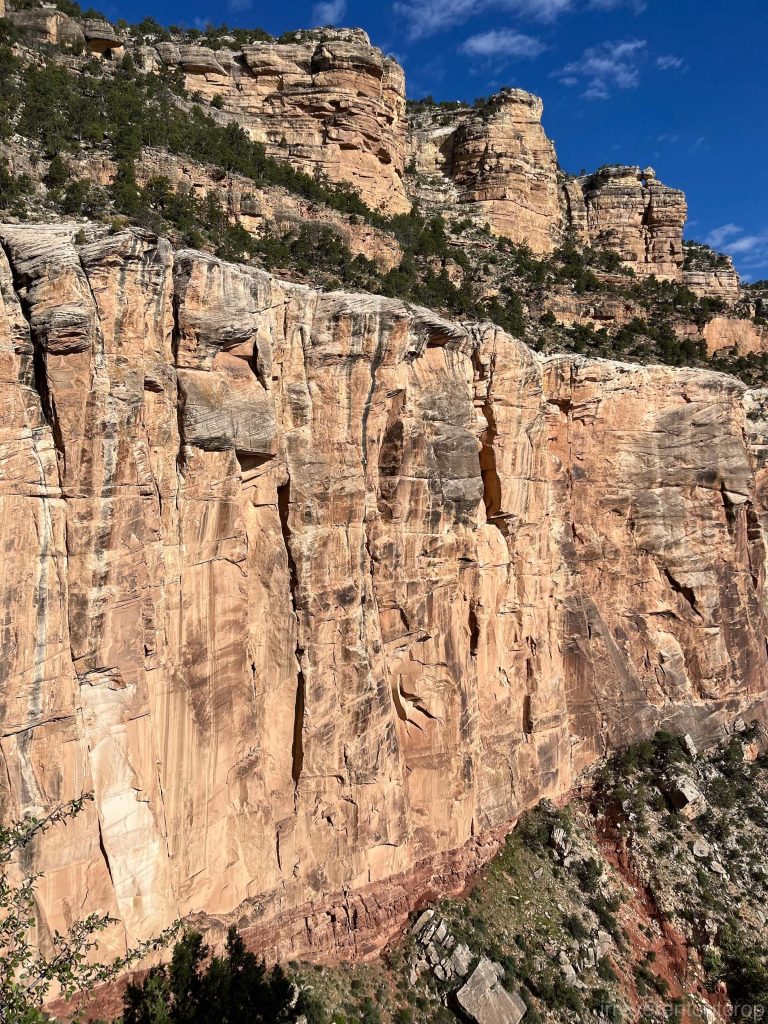

The Coconino Sandstone cliffs stand right next to us while we were on the trail. It’s quite intimidating. The rock is light in color, with highly developed vertical jointing, making the cliffs almost vertical and completely devoid of vegetation. Up close, we can clearly see the distinct cross-lamination in the cliff face.

The unconformity between the bottom of this light yellow sandstone layer and the top of the red shale layer below is also very distinct.

4. Hermit Shale

This shale unit is dark red in color and formed during the early Permian period. Its texture is relatively soft, and it has a high iron oxide content, which gives it its distinct dark red color. It visually stands out significantly from other Permian layers in the stratigraphic sequence. But I am not clear whether the oxidation process occurred during the deposition phase or later during the lithification phase…

Shale is also an easily erodible rock type, so this Hermit Shale Formation rarely forms large cliffs and is considered a slope-former.

Carboniferous formations

Continuing downward from the Permian formations, we then encounter the older Carboniferous formations.

5. Supai Group

The Supai Group was formed during the late Carboniferous period. The term “group” here refers to the fact that it can be further subdivided into different formations and units. However, because this section is heavily vegetated, the rocks don’t have clear, unified characteristics, making it difficult to distinguish them.

Similar to the previous Hermit Shale formation, this mixed layer has a reddish hue and is also a slope-former. As a result, the boundary line is not very distinct, and it feels like a continuous stretch of a larger dirt slope.

The Supai Group is rich in fossils. For example, we noticed a fossilized footprint from over 300 million years ago, located right next to the hiking trail.

6. Redwall Limestone

The Redwall Limestone unit was formed around 340 million years ago during the early Carboniferous period. It is a hard, erosion-resistant rock, with a high iron oxide content, giving it a deep red or brown color. This section is a typical cliff-former, with many steep cliffs and towering rock faces, creating a truly spectacular view.

Cambrian formations

Beneath the Redwall Limestone of the Carboniferous period, there is theoretically a relatively thin and irregular layer called the Temple Butte Formation, which was deposited during the Devonian period. However we couldn’t recognice it during our visit. It’s also possible that this section of the Bright Angel Trail doesn’t pass through that formation.

Then the geological sequence skips over the Silurian and Ordovician periods, directly reaching back to the Cambrian period. This gap of about 165 million years might have resulted from a lack of deposition, or it could have been completely eroded after deposition. Considering that land plants only appeared in the Silurian period, the erosion rate of rocks from the Silurian, Ordovician, Cambrian, and Precambrian periods was likely quite high.

7 & 8. Muav Limestone and Bright Angel Shale from Cambrian time

The Cambrian formations consist of the Muav Limestone at the top, which formed over 500 million years ago. It is primarily a cliff-former, continuing the cliff faces of the Carboniferous Redwall Limestone. The thickness of this layer varies across different sections of the canyon.

The Bright Angel Shale unit sits right below the Muav Limestone. It is a slope-former with a lighter color. Being closer to the canyon floor, it has more available moisture, allowing for more vegetation coverage.

The basement rocks

At this point, we have reached the canyon floor. It is surprisingly lush and vibrant with vegetation. The rocks here date back to before the Cambrian Explosion!

9. The oldest metamorphic bedrock deep in the canyon is the 1.7-billion-year-old Vishnu Schist

Due to the abundance of loose soil and dense vegetation at the canyon floor, we couldn’t get a detailed look at the exact location of the 1.2-billion-year-gap unconformity between the Cambrian shale and the Proterozoic schist, but we crossed over it anyway. This legendary unconformity is actually more clearly visible when we look at the North Rim from a distance.

However, what was unmistakable was that we began to encounter rocks that no longer looked sedimentary. The schist here is hard, with colors ranging from gray to light gray.

After a short rest, we turned around and started our hike back. The day was still bright by the time we reached the top. I think we did a pretty good job!

Conclusion

Hiking down the Grand Canyon was an incredibly exciting journey, and with the spring weather being just right— not too hot, not too cold. It was very pleasant.

A few important things to note:

- The uphill return journey generally takes about twice as long as the downhill descent, so it’s important to plan your time and energy wisely.

- During peak tourist season, there are water refill stations at the canyon floor, so you don’t need to carry excessive amounts of water with you.

- The hiking trails are all dirt paths, but with many well-built stairs, and they are generally wide enough to be safe.

- While the official national park service website strongly advises against doing a round-trip in one day, it’s absolutely doable for those with good physical condition.

The end. Thanks for reading!