During my trip to the Hexi Corridor in September 2024, I visited the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang. I was quite amazed by the caves that I would like to insert this post of cultural topics here, not quite related to nature or geology like most of the other posts on my website.

Dunhuang is located in the northwest part of Gansu Province, at the crossroads of the ancient Silk Road. It is the westernmost of the classic “河西四郡” (Han Dynasty’s “four counties to the west of the Yellow River” – Wuwei, Zhangye, Jiuquan, and Dunhuang). Buddhism passed through here when it was introduced to China.

The excavation and statue-making of the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang lasted for about a thousand years, from the Southern and Northern Dynasties (420-589 AD) to the decline of the Silk Road in the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368 AD). The murals are the most magnificent part of the caves, supplemented by statues, and the content is rich and extensive. Not only are there a large number of Buddhist stories and history, but also folk cultural customs of various dynasties. It is an important cultural relic for the study of religious and art history in China.

The current regulations prohibit taking photos in the caves, so there are no photos of the interiors of caves in this post. However, I saw several 1:1 cave replica exhibition halls in the museum (including Cave 285), and people are allowed to take photos there. Taking photos outside of the caves are fine though.

We bought ordinary tickets for the peak season, which allow us to see 8 caves according to the guide’s preferences (ordinary tickets can see 12 caves during off-season; emergency tickets can only see 4). We did not buy extra “special tickets” to see “special caves”. When entering the ticketed area for the first time, each tour guide will lead a dozen people to form a group. Since each cave is protected by a locked iron door (donated by Mr. Run Run Shaw), and there is no light inside, you literally can’t see any cave without a tour guide.

After seeing the first 7 caves included in the ordinary ticket, we didn’t rush out to see the last one, Cave 96 (a giant Maitreya Buddha statue), but stayed in the ticket area for another while so that we could go back to “revisit” some other caves, which means we could actually join other groups and listen to other tour guides’ explanations in caves that our first tour guide didn’t show us.

Memorizing the order of dynasties in the Dunhuang area is very important for understanding the content and art forms in the caves:

- Early period of the caves: Northern Liang (one of the “Five Barbarians and Sixteen Kingdoms” during the Eastern Jin Dynasty 304-439 AD), and then Northern Wei, Western Wei, and Northern Zhou during the “Southern and Northern Dynasties” (420-589 AD);

- Heyday: Sui (581-618 AD) and Tang (618–907 AD);

- “Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms” (907-979): Tubo, Guiyi Army Jiedushi, Shazhou Uighur

- Decline: Western Xia (1038-1227 AD) and Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368 AD). This was also the period when the Silk Road gradually declined.

Later, during the Ming Dynasty, Dunhuang became a frontier nomadic area. Statue-making activities stopped, but there was not much damage. During the Qing Dynasty, due to reclamation activities, economic activities in the surrounding areas rebounded. During the period of management by Taoist Wang Yuanlu in the late Qing Dynasty, many Buddha statues were rebuilt with poor quality, and a large number of scriptures were stolen by thieves from Britain, France and other western countries. After the collapse of Qing Dynasty, many murals were destroyed and pillaged by the White Army of Tsarist Russia and an American dude named Langdon Warner. The caves were not protected until the 1930s and 1940s.

Before I came to Dunhuang, I was not too familiar with the history and political situation in the Hexi Corridor region during the “Five Barbarians and Sixteen Kingdoms”, “Southern and Northern Dynasties” and the “Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms” periods. I definitely learned quite a lot about those during this visit.

When visiting various caves, I found that several important concepts were often mentioned by the tour guides:

- Jingbian paintings: refers to paintings depicting the content of Buddhist scriptures or stories of the Buddha. Most of the contents displayed are grand scenes, various characters, and exquisite details of clothes and decorations. Many murals in the caves are Jingbian paintings, which is a major feature of Dunhuang.

- Feitian / apsara: refers to the heavenly beings flying around the Buddhas in Buddhism. In Jingbian paintings, they often appear in the form of graceful dances or playing various musical instruments.

- Patrons: refers to people who donate money to carve caves. There are portraits of donors in the murals of many caves.

- Caisson / “algae wells”: refers to a ceiling decoration structure in traditional Chinese architecture. The ceiling is concave upward like a well, and the four slopes are decorated with algae patterns. Caisson is an important part of the Dunhuang Caves. The caisson on the top of each cave is different. Some impressive examples include the “three hares with shared ears” caisson, the “lotus with Feitians” caisson, etc.

- Central column: The central column cave is the main form of the early caves. It’s designed in a way that pilgrims can worship and walk around the column.

- Thousand Buddhas: A very common type of Buddha mural in Mogao Caves, composed of hundreds or thousands of small Buddha statues in sitting or standing positions arranged closely together.

There are 735 recorded caves in Mogao Caves, of which 492 have murals and sculptures. The following is a simplified introduction to the caves I visited this time, which can be used as a reference.

First of all, there are three caves that all ordinary ticket holders will visit:

- Cave 16: the largest cave in Mogao Caves. Its early murals were painted during late Tang Dynasty, which are very exquisite. The statues were rebuilt in the Qing Dynasty and the quality is not quite matching with their Tang dynasty peers.

- Cave 17: located on the north wall of the corridor of Cave 16. It is the world-famous “Cave of the Buddhist Scriptures”. There is only one statue left in it now. Most of the scriptures were stolen by thieves from the Britain and France in late Qing Dynasty, and the rest were preserved in several museums in China.

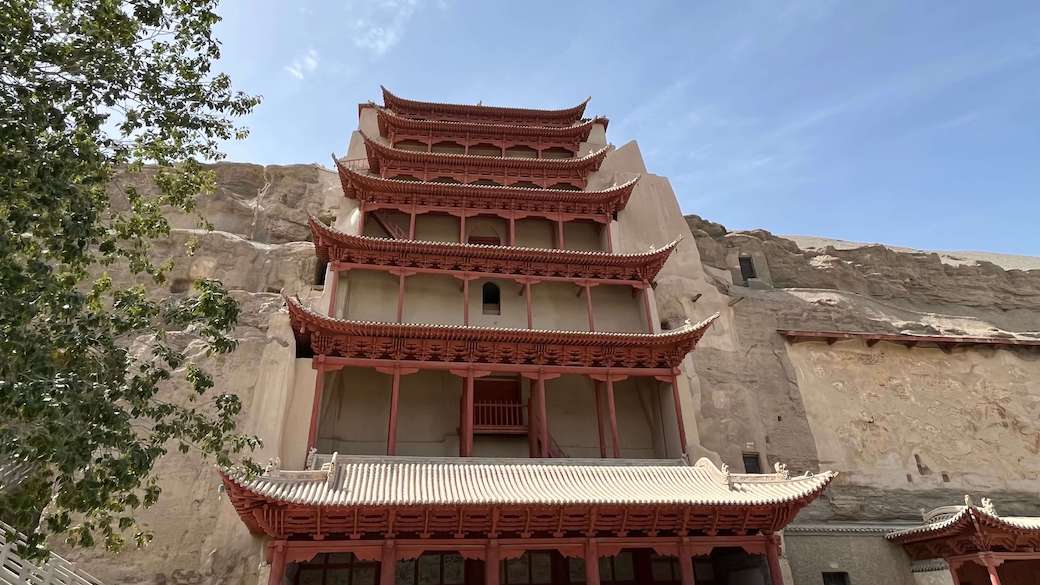

- Cave 96: the exterior of the cave is the iconic building of Mogao Caves, the “Nine-story Pagoda”. Inside Cave 96 is a giant Maitreya Buddha statue. Cave 96 is the last cave visited by ordinary ticket holders while the first cave visited by emergency ticket holders. It’s always crowded inside.

The following also lists the other caves we visited – the 5 caves that we visited with our assigned tour guide, plus another 13 caves that we visited by following other tour guides; arranged in numerical order. Each cave is unique and worth a closer look to be honest, though I still can’t help but give an additional “rating” based on my own subjective personal experiences (★ Good, ★★ Highly recommended, ★★★ Really Impressive. The tour guide’s explanation can actually significantly affect visitors’ impression of the caves)

Cave 61 ★★★: Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period. This is a huge merit cave built by Cao Yuanzhong (the governor of Guiyi Army) and his wife. The back wall has a panoramic view of Mount Wutai– a sacred Buddhist site in Shanxi Province. The two walls at the front have wonderful murals of patrons from Cao family. The detailed illustrations of female clothing, jewelry, makeup, etc. are quite exciting. This cave is very popular with various tour guides, so there are always loads of people coming in and out. Its iron gate is basically never locked. The cave is so large that it can easily accommodate 2-3 groups of people at the same time. Since each tour guide is limited by time and can only pick a small part of the mural to talk about to visitors, so staying a little longer and listening to more tour guides can learn many different stories.

Cave 79 ★: The heyday of the Tang Dynasty. Among the thousands of Buddhas on the top of the cave, there are many line-drawing style naked children’s paintings. Their postures are active and the images are really vivid.

Cave 112 ★★: The middle Tang Dynasty. The statues were lost, but the Jingbian painting murals are exquisite, with the famous figure of “playing pipa behind the back“. The upper part of the murals mostly shows Tang Dynasty buildings, the middle part is the Buddha and Bodhisattva, and the lower part is various Feitians dancing and playing musical instruments.

Cave 237 ★★: The middle Tang Dynasty. There is a Tubo tribute picture, which shows the detailed Tibetan noble costumes. The ceiling is a famous “three hares with shared ears” caisson. After the visit I learned that there was a two-headed Buddha figure in the murals, but I didn’t see it during the visit.

Cave 244 ★★: Late Sui and early Tang Dynasty. There are wonderful original statues from the Sui and Tang Dynasties, which are the earliest “Three Buddhas (past, present, and future)” themes in Mogao Caves – there are three groups of statues in front of the east, south and north walls of the cave, with a total number of eleven statues.

Cave 251 ★★: Northern Wei Dynasty. A large number of early Feitian/apsara portraits. The Feitian murals have obvious masculine characteristics; the skin color pigments got much darker due to aging; and the “small character (小) face” painting method is commonly used.

Cave 257 ★★★: Northern Wei Dynasty, the murals contain “Deer King Jataka painting“, which is the original inspiration of a famous Chinese story “A deer of nine colors“.

Cave 259 ★★: Many original statues from the Northern Wei Dynasty. The Buddha statues have peaceful and tranquil faces, and the one near the entrance has a charming smile, which is called “Mona Lisa of the East“.

Cave 285 ★★★: A rare cave from the Western Wei Dynasty. The top of the cave is a square canopy-style caisson. The four walls are painted with not only images of Buddhist guardian gods such as the Cintamani, the Lishi, and the Apsaras, but also traditional Chinese mythological gods such as Lei Gong “the thunder god”, Fuxi, and Nuwa. Cave 285 is also known as the “Thousand gods palace“. The theme painting on the side walls is “The Story of Five Hundred Robbers Becoming Buddhas”. There is a 1:1 replica of this cave in the museum, and people can take photos there (as shown below).

Cave 323 ★★★: Early Tang Dynasty. The most distinctive feature is the “comic strip” of Buddhist historical sites in the cave. On the north wall, there is the famous mural of “Zhang Qian’s mission to the West“. The central part of the mural of “The Golden Statue of Yangdu in the Eastern Jin Dynasty Exiting the Islet” on the south wall was stolen by Langdon Warner in 1924 and is now preserved at Harvard University.

Cave 328 ★★★: A group of exquisite original Tang Dynasty statues. The dynamics of the Buddha’s arms and the folds of his clothes are very delicate. On both sides of the Buddha statue are the Buddha’s two disciples, Kasyapa and Ananda, with vivid facial expressions and body postures.

Cave 329 ★★: Early Tang Dynasty. The “lotus with Feitian” caisson is extremely exquisite. Most of the murals are also original Tang Dynasty works. The statues were rebuilt in the Qing Dynasty with not-too-good workmanship though.

Cave 334 ★: Excavated in the early Tang Dynasty. The interesting thing about the statues in this cave is that the upper body of the statues were rebuilt in the Qing Dynasty in a crude way, but the lower bodies are the original version from the Tang Dynasty, with exquisite workmanship and meticulous depiction of the silk texture. The craftsmanship of the two generations is in sharp contrast.

Cave 340 ★: Early Tang Dynasty. The cave top has a peach-shaped lotus flower pattern caisson.

Cave 390 ★★: “Canopy Cave” of the Sui Dynasty. Each Buddha in the Thousand Buddhas is very large and has a canopy, and none of them are the same. The statues were rebuilt in the Qing Dynasty.

Cave 401 ★: Sui Dynasty. The cave is surrounded by a large number of Feitians with different postures.

Cave 427 ★★: It was excavated in the Sui Dynasty and consists of front and back rooms. The statues on the both sides of the front room are the Heavenly King and the two generals “Hengha”. The inscription of the Song Dynasty renovation has been preserved, and the wooden cave eaves building outside the cave is also left over from the Song Dynasty, which is rare in Mogao Caves.

Cave 428 ★★★: A rare cave from the Northern Zhou Dynasty. On the east wall, there is a comic strip-style depiction of the story of Buddha’s previous life: Prince Sattva sacrificed his body to feed a family of tigers. There are about 1,200 portraits of patrons painted at the bottom of the wall, which shows that this cave’s excavation was the result of the concerted efforts of many sectors of the local society during the Northern Zhou Dynasty. The style of the Feitians is similar to that of other caves from the Northern and Southern Dynasties, with obvious male characteristics. The roof is a herringbone slope with honeysuckle flower patterns.

Some general thoughts after the visit:

- The images of Buddha and flying apsaras in the caves constructed before Sui dynasty were quite masculine, with strong traces of styles from ancient India. Most of the caves during this period have central columns in the middle for pilgrims to circle around.

- Sui Dynasty only lasted 38 years with two emperors, but more than 100 caves were constructed during Sui Dynasty. What a productivity! The depiction of flying apsaras gradually softened as more Chinese painting styles were incorporated during this period.

- The artistic achievements reached their peak during the Tang Dynasty. In the statues and murals, the exquisite and detailed depiction of figures’ expressions, postures, costumes, and jewelry is significantly superior to those from other dynasties. Particularly in the case of statues like Cave 334, the upper body was repaired after the Qing Dynasty, while the lower body is an original work from the Tang Dynasty, creating a sharp contrast that is immediately noticeable.

- During the Five Dynasties, Tubo and Guiyi Army ruled successively, and the statue-making activities continued. The contents of the murals added lots of images of famous noble patrons at that time.

That’s it! Wish all of you who are going to Mogao Caves in the future the best luck in getting tickets (it’s quite competitive since there is a quota of visitors for each day)!