I’ve often pondered why so many destinations that captivate my imagination lie perpetually out of reach. No matter where I’ve lived, these places remain scattered to opposite ends of the Earth. Are these far-off vistas truly more breathtaking than the landscapes nearby, or does their appeal stem solely from the novelty of their remoteness?

1. “The unattainable always makes you restless”

Human psychology is wired to crave the inaccessible—unmet goals linger in our minds far longer than those we achieve (a phenomenon known as the Zeigarnik Effect). Distant places, like a carrot dangling eternally beyond a horse’s reach, taunt us with their unattainability.

Yet even if we finally arrive at these longed-for destinations, the thrill of attainment fades swiftly. Our minds adapt to new surroundings with startling speed, resetting our baseline happiness—a process psychologists term hedonic adaptation. The restless heart, unsatisfied, soon redirects its yearning to another horizon, perpetuating an endless cycle of desire.

From an evolutionary lens, this restless pursuit is adaptive: it fuels exploration, innovation, and survival.

2. Biophilia – the innate bond with nature.

55% of the global population lives in cities nowadays. The urbanization rates are even higher in industrialized regions. Urban centers excel at efficiency—maximizing convenience while minimizing per capita energy use. But beneath this engineered pragmatism, our biology rebels.

The biophilia hypothesis, coined by biologist E.O. Wilson, argues that humans possess an innate, genetic affinity for nature. After prolonged immersion in concrete jungles, we instinctively crave reconnection with wildness. Ancient cultures universally revered natural forces—sun, moon, mountains, forests, and creatures—a testament to humanity’s primal bond with the Earth.

Moreover, untouched landscapes thrive farthest from urban sprawl. These remote ecosystems—pristine and unmarred by human intervention—offer profound psychological restoration. Their isolation and raw beauty remind us of nature’s grandeur, grounding us in humility and wonder.

3. Curiosity and thirst for knowledge.

Our drive to explore distant places is rooted in a biological trait: curiosity. From an evolutionary standpoint, early humans who lacked curiosity for the unfamiliar likely perished in Africa’s jungles long before venturing beyond them. It was this innate, genetic hunger to discover the unknown that enabled our species to eventually inhabit nearly every corner of the Earth.

Distance magnifies curiosity. The farther a location is from our daily routines, the more starkly its environment contrasts with our own—and the more powerfully it ignites our desire to explore. Take elevation as an example: roughly 75% of the global population lives below 500m (1,600 ft). As someone who has always resided in flatlands, I’m struck by how rugged mountains and sheer cliffs—landscapes so alien to my everyday experience—evoke an almost primal sense of awe.

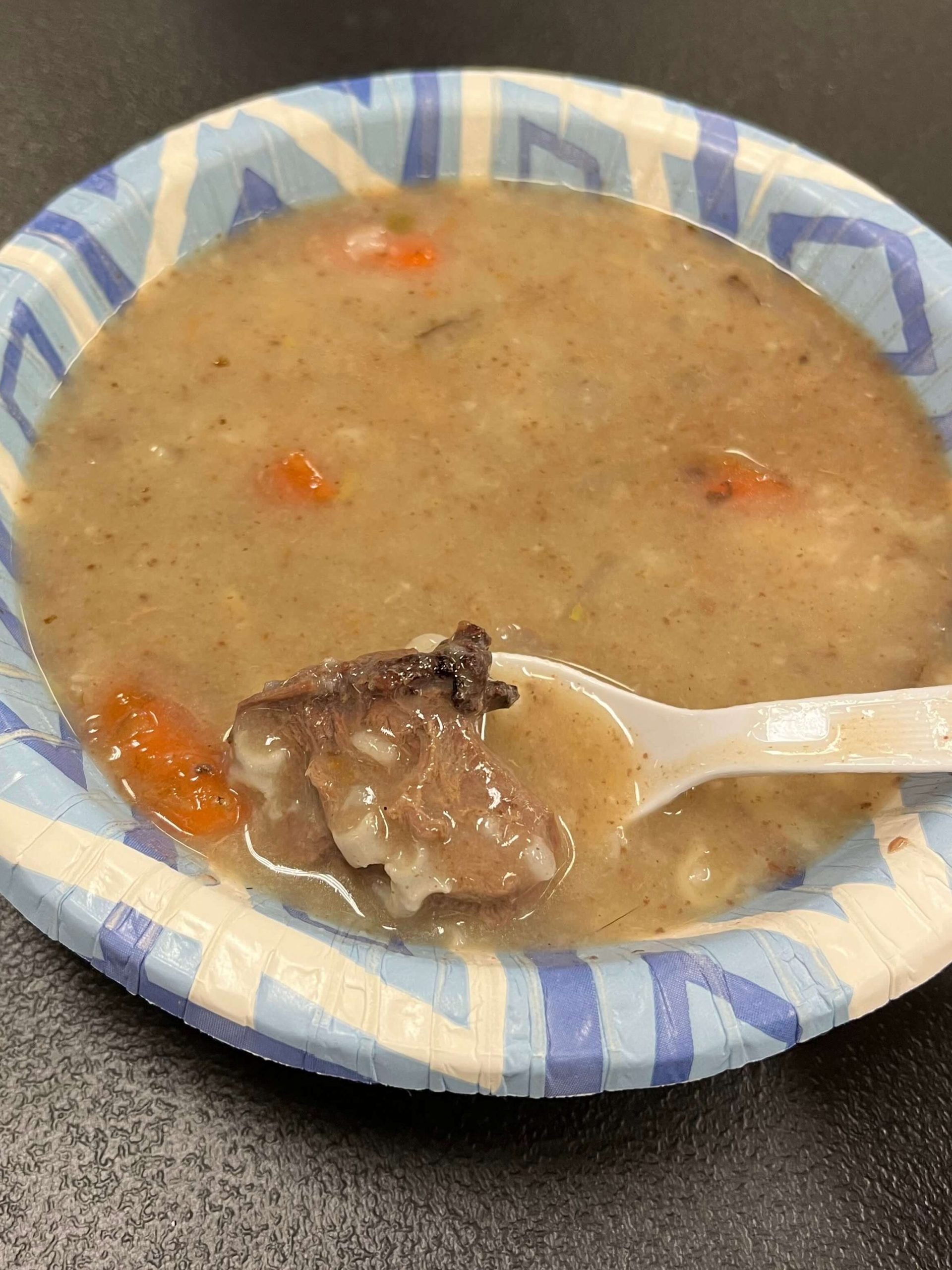

This quest for novelty extends to cultural perspectives too. The farther we venture from home, the more pronounced the cultural contrasts become—differences that hold an irresistible allure. Natural isolation amplifies this phenomenon, fostering extraordinary cultural diversity in remote pockets of the world like high mountains, islands, and arctic regions. Geographical seclusion has long compelled societies to develop distinct ways of life—from architecture adapted to harsh climates to cuisine shaped by limited resources. These natural barriers didn’t just inspire innovation; they historically functioned as fortresses that shielded inhabitants from invading armies and cultural homogenization, allowing languages and traditions to evolve in protected ecosystems of human creativity.

In contrast, floodplains of temperate continental regions, fertile river deltas, or strategic seaport cities may have environments conducive to civilization development and can support higher population densities. Social structures and technological advancements often evolve more rapidly in these areas, which may become centers of civilization. However, they are also among the first to suffer when conflicts arise.

Borders

Another specific type of “distant place” that fascinates me is the “border”. This could be a natural boundary—coastlines, watersheds, tectonic plate divisions, geological strata shifts—or a human-made one, such as national or provincial borders and settlement edges. Reaching these frontier zones often requires venturing into remote areas.

Natural boundaries represent “convergence” and “collision,” frequently giving rise to dramatic landscapes. The stories they reveal—through both human history and natural forces—tend to be more intricate and compelling than those found in more uniform regions.

Right: while hiking down to the bottom of the Grand Canyon in spring 2024, I passed a stunning example of an unconformity between the beige-colored Coconino Sandstone and the deep red Hermit Shale. This contrast reflects a dramatic shift in climate during the early Permian period, evident in the differences in sediment grain size and iron oxide content.

Modern political borders are often the result of historical developments, with tumultuous events behind them that are worth exploring. As a visitor, understanding these borders can add a deeper dimension to the journey.

Borders frequently drive cultural divergence, leading to distinct linguistic, social, and behavioral differences. This process tends to unfold more rapidly in border regions than in stable cultural centers, where traditions evolve more gradually.

One example is the migration of Koreans northward into Qing China and the Russian Empire beginning in the 19th century. Despite enduring over a century of war and upheaval, these communities preserved their ethnic identity while continuously adapting to local influences. After the Korean Peninsula was divided in 1953, the Korean language in the South absorbed numerous foreign words, while the North remained more linguistically conservative, widening the gap between the two dialects. Meanwhile, the Korean spoken by ethnic Koreans in China remains closer to the North Korean dialect but has also been influenced by Chinese, while most Korean descendants in Russia can only speak Russian.

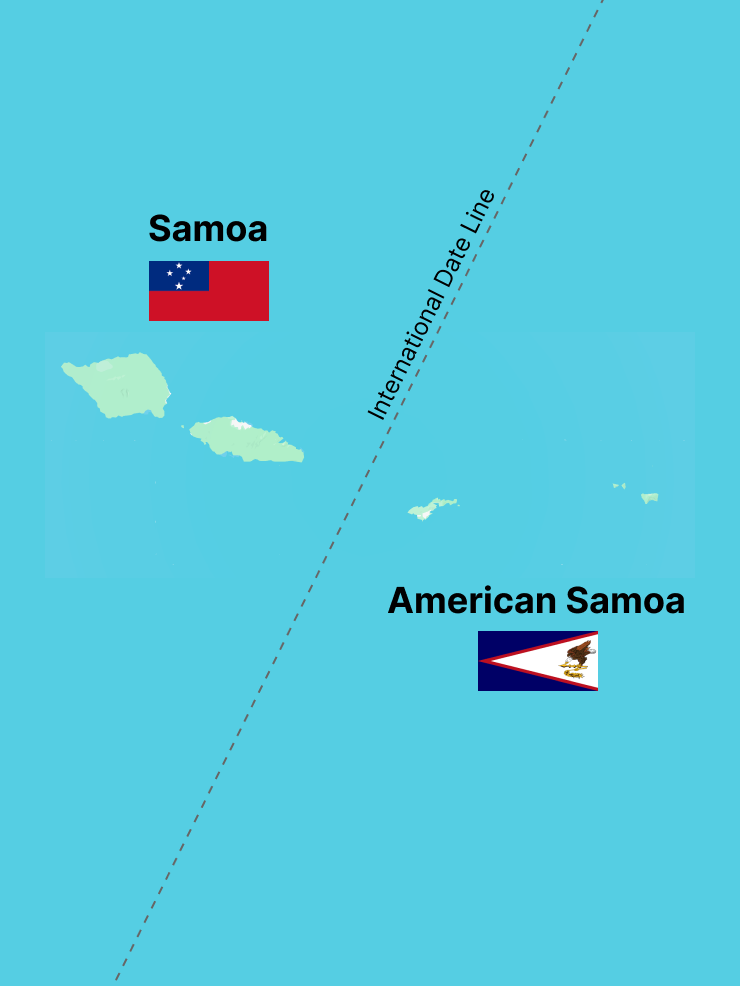

Another interesting example is the Samoa Islands in the South Pacific. The indigenous Samoans are a subgroup of the Polynesians, but the islands were divided by colonial powers into two parts in 1899: Western Samoa was under German occupation, then became a New Zealand colony after World War I until it gained independence in 1962 (now known as the Independent State of Samoa); while Eastern Samoa was taken by the United States and remains American Samoa. As a result, although both regions’ residents speak Samoan, their English accents differ—those in the west tend to adopt British accent, while those in the East lean toward American pronunciation.

Before colonization, Western Samoa, with its larger landmass and flatter terrain, served as the region’s agricultural hub, while Eastern Samoa, characterized by its rugged mountains, was often used as a place of exile. However, because of the direct investment from the US government and the US military nowadays, American Samoa’s per capita income is three times higher than that of the western side. This economic disparity has led many Western Samoans to seek work opportunities in the east.

After entering the 21st century, Western Samoa not only changed the driving direction from the right-hand side, which was used during the German occupation, to the left-hand side to facilitate the import of cheap cars from Japan and Australia, but also “moved across” the International Date Line, shifting from UTC-11 to UTC+13 to align its time zone with key trading partners in the Asia-Pacific region. Meanwhile, the eastern side retained the U.S. driving system and the time zone of the Western Hemisphere.

Sub-Saharan Africa offers countless examples of how national borders were arbitrarily drawn by European colonizers during the colonial era, resulting in the division of ethnic groups and tribes.

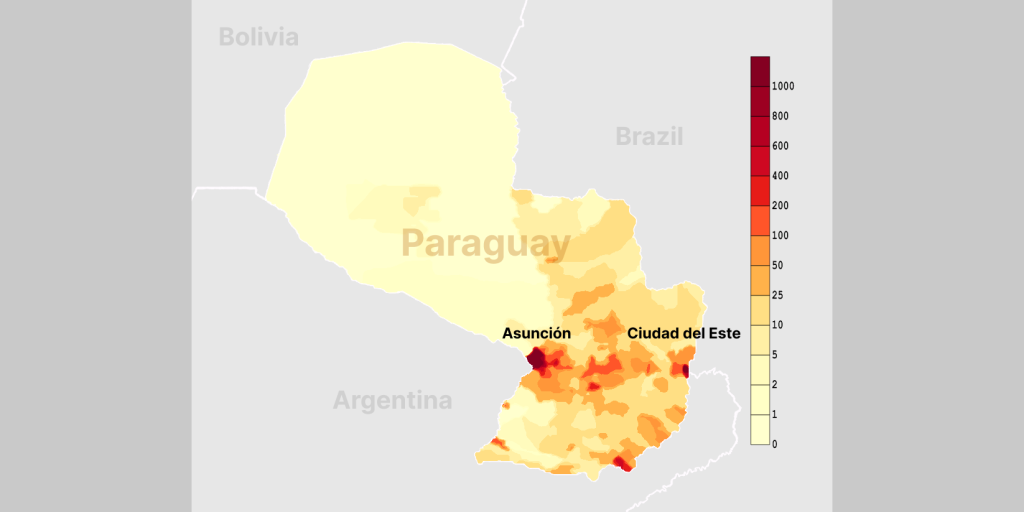

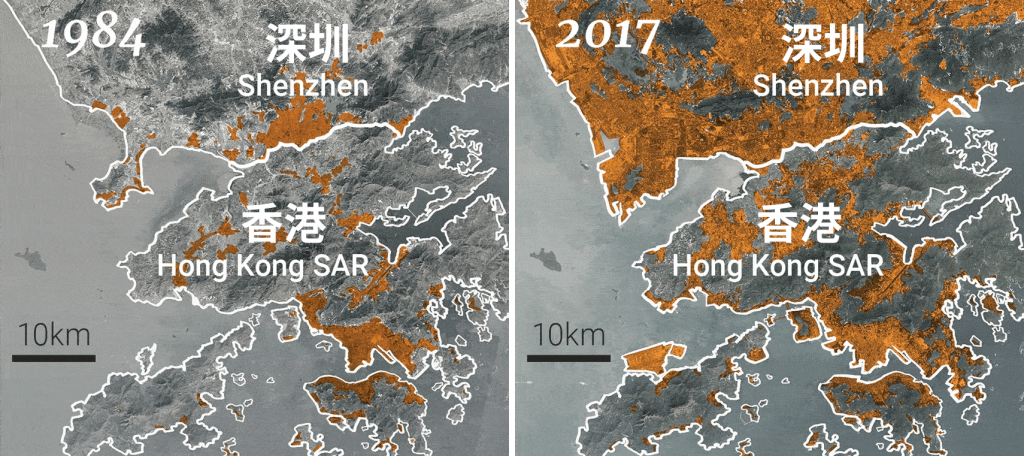

The existence of borders and the differences in policies on either side also generate unique economical developmental phenomena along the borders. This is evident in places like Paraguay and Shenzhen, where contrasting approaches have sparked curiosity and fueled further exploration of these borderlands.

Whether it’s the longing for distant places we can’t quite reach, the pull of nature, or the fascination with cultural differences, all of these desires stem from our inner impulses. Yet, in the age of globalization, two opposing forces—one pushing us forward, the other pulling us back—shape the direction of our journeys.

4. Globalization’s “Push” and “Pull”

The “push” force comes from infrastructure and convenience that benefits the general population: air travel, high-speed rail, online payment systems, navigation software, translation apps, and more. Technological advancements have made travel and exploration, once reserved for the elite, accessible to a much wider audience.

The “pull” force, on the other hand, is the growing cultural homogenization resulting from economic powers exerting influence over weaker regions. This homogenization, in essence, erases the uniqueness of places that we crave and are curious about, posing a major challenge to the survival of local cultures.

Homogenization is driven by capital interests and long-term ideological indoctrination. The commodification of individual human beings leads to standardized behaviors, creating a cycle where consumption becomes self-perpetuating—exactly what capital seeks to achieve.

For instance, Disney’s extensive marketing over the years has made it a common expectation for many people traveling to places like Los Angeles, Florida, Tokyo, Shanghai, or Paris to spend additional days and money at Disney theme parks. People willingly spend outrageous sums on tickets and parking fees just to repeat the experience they’ve had before in a man-made bubble on the other side of the world. While it makes sense for a local to visit a nearby theme park as a casual escape, I find it hard to justify a Shanghai resident traveling all the way to Paris just to visit Disneyland. That feels like a waste of both time and money.

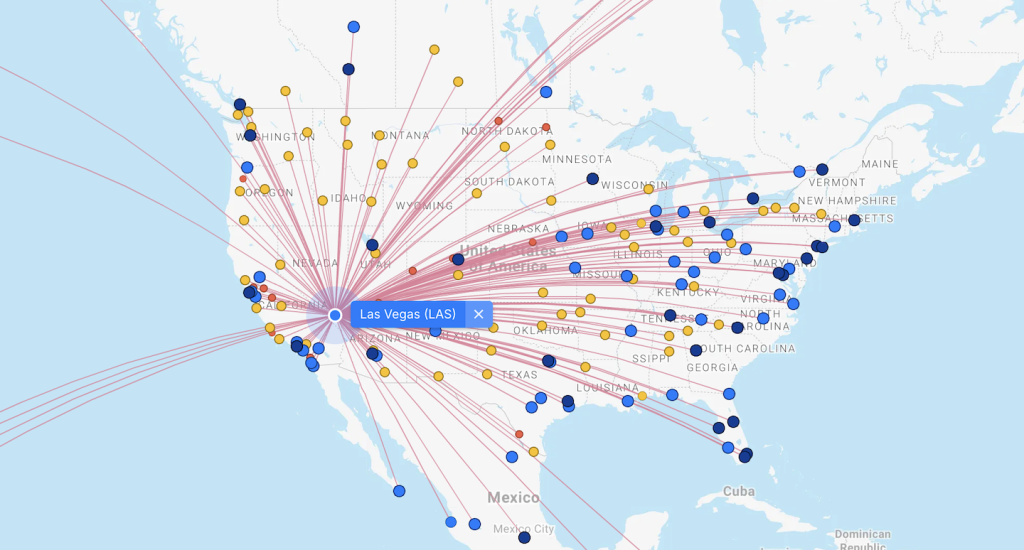

Las Vegas, the ”Sin City” that rises from the Nevada desert, is another classic example. Decades of marketing and promotion have fueled endless fantasies about the city’s extravagant lifestyle. When considering a vacation or anniversary celebration, “Sin City” often springs to mind first. Even today, airlines continue to add more direct flights to Las Vegas every year. With a population of only 660,000 (barely considered a town in East Asia), Las Vegas has managed to connect almost every city in North America, and even boasts direct flights from numerous cities in Europe, Japan, and South Korea.

Advertising, movies, and TV shows relentlessly reinforce the commercialized concepts of “tourism” and “vacation”— the images of staying in grand resorts, lounging by pools, playing golf… A trip to the beach must be paired with a yacht ride; a hotel without a pool isn’t considered upscale; a vacation isn’t relaxing without a jacuzzi; and golf courses must be built regardless of local climate. In reality, these specific material scenarios were originally shaped by the commercial models of developed countries in temperate, humid regions (i.e., Western Europe and the East Coast of North America). Yet today, these standards have been mindlessly applied to tourism development across the globe— after seeing glaciers in Greenland, one is expected to play a round of golf and then lounge by a round-shaped pool with a cocktail in hand; after climbing sand dunes in the Sahara Desert, one is also expected to play golf and lounge by a round-shaped pool with a cocktail in hand… People who have been inundated with these ideas over the years naturally accept them without question.

Take golf as an example — the southeastern coast of Scotland, where golf originated, has rolling hills and an average annual rainfall of around 700mm (28in). The temperate maritime climate keeps the grass lush year-round. Meanwhile, Palm Springs, a desert town in the heart of California’s desert, experiences an annual rainfall of only 120mm (4.6in), with most of it falling during the winter months (Dec-Feb), leaving the scorching summer months completely dry. Yet, it is home to over 130 golf courses, making it one of the regions with the highest density of golf courses in the world! This shortsighted business decision and forced application of a model disrupt the native ecological balance, waste resources, and stifle other potential, unique desert landscapes and activities in the Palm Springs area. It fails to integrate with or respect the native environment, making it a major flaw in its approach.

When profit-driven development reaches its extreme, it leads to what is termed “enclave tourism”: the creation of isolated “bubbles” that separate tourists’ activities from the surrounding environment and social space. These include all-inclusive resorts, gated vacation communities, and similar self-contained spaces.

Enclave tourism is largely operated by American and European hotel corporations in tropical developing countries, with sprawling projects often occupying prime coastal areas. Prominent cases include:

- The Caribbean: Cuba’s Varadero Peninsula, the Dominican Republic’s Punta Cana, and Jamaica’s Montego Bay;

- Central America: Mexico’s Los Cabos and Cancún, and Costa Rica’s Gulf of Papagayo;

- The South Pacific: Private island resorts in Fiji and French Polynesia (including Tahiti and Bora Bora);

- The Indian Ocean: The Maldives and Seychelles;

- Ecuador: Luxury cruises in the Galápagos Islands, charging thousands per person.

- …

Even some developed nations are not exempt, such as Spain’s Costa del Sol and Portugal’s Funchal in Madeira, where gated resorts dominate the landscape.

To those who argue:

“I live somewhere with little sunshine, I’m too busy to plan trips, and I just want to relax on a sunny beach without hassle. If I can afford an all-inclusive stay, what’s the problem? This model works perfectly for me.”

My unpopular opinion would be: while it may sound harsh, individuals who channel their energy into serving corporate interests—leaving no capacity to seek meaning beyond work—and who then, under the guise of “laziness,” willingly funnel their earnings back into the very system that exhausts them, are capitalism’s ideal heirs. Their choices reinforce a cycle where profit eclipses people, and isolation replaces genuine connection.

5. Seeing through the illusion

By understanding the profit-driven machinery behind the “tourism industry” and stepping out of the constrained framework, we’ll realize a world brimming with under-appreciated experiences. With today’s advanced information networks, even modest research into a region’s natural history or cultural legacy reveals that corporate-backed attractions- heavily marketed as must-sees- rarely hold the deepest stories or most meaningful encounters.

This realization brings tangible advantages: freedom from crowds, wasted expenses, and superficiality. You’ll distinguish authentic heritage from fabricated imitations—spotting which “ancient towns” are genuine versus artificial replicas; identifying true Song Dynasty murals amid newly constructed temple complexes; recognizing glacial valleys versus mined-out quarries disguised as natural canyons. Putting in this effort is worthwhile.

When we focus on what’s real rather than what’s hyped, we often find hidden surprises. Here are a few examples that recently left a deep impression on me.

On my trip to Newfoundland to see glaciers, a friend familiar with the area reminded me that when driving back to Gros Morne National Park after seeing the icebergs near Saint Lunaire-Griquet, we’d come across some layered sedimentary formations created by cyanobacteria: thrombolites. These clotted microbial structures represent Earth’s earliest lifeforms, dating back 3.5 billion years, yet few remain today.

While cross-referencing Alaska’s national park maps with regional flight routes, I noticed a small town called Anaktuvuk Pass nestled within Gates of the Arctic National Park—reachable by air. After contacting the local airline, I was pleasantly surprised: not only were the prices reasonable, but a friendly staff member also enthusiastically recommended the route, having flown it herself and vouching for its stunning views. I booked the flight, and true to her word, the experience matched her praise.

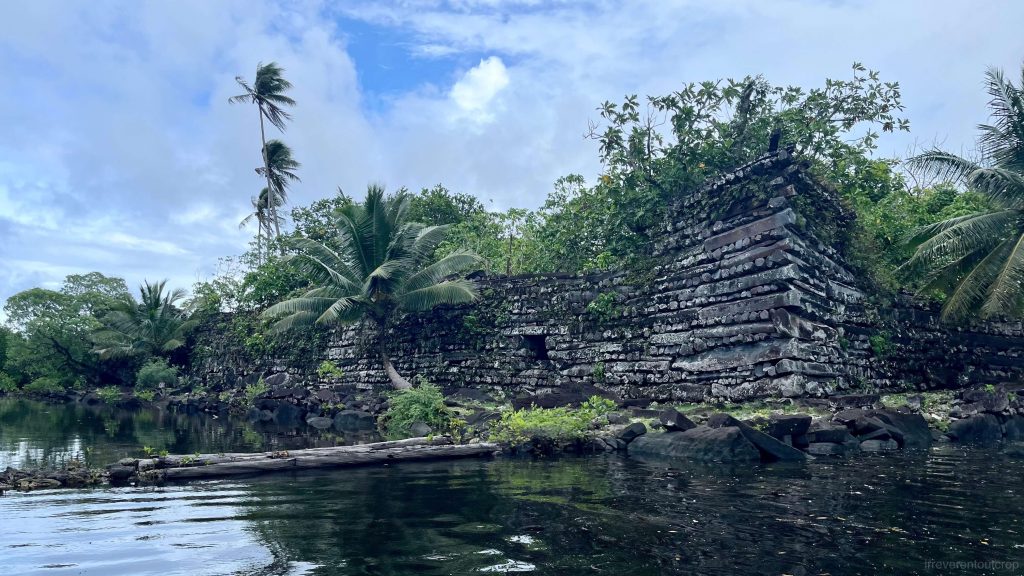

While researching Nan Madol, I learned that United Airlines operates the “Island Hopper”—a unique flight route connecting Micronesia’s scattered islands. Though cash prices are shockingly high, redeeming miles for this journey remains surprisingly affordable, even after years of mileage program devaluations. Better yet, the route allows stopovers, and I stumbled upon an unexpected gem: a chance to explore Kosrae Island along the way.

Exploring lesser-known landscapes often means confronting underdeveloped infrastructure and unpredictable logistics. Travelers might grapple with nonexistent or outdated online information, handwritten reservation systems, cash-only economies, and transportation networks (roads, flights) vulnerable to weather disruptions—leading to frequent delays or cancellations.

A prime example of such a destination—one I’ve long wanted to visit but haven’t yet—is Alaska’s Aleutian Islands.

Stretching over 1,900 km (1,200 miles) along the northern edge of the Pacific Plate’s subduction zone, the Aleutians rank among Earth’s most volcanically active regions, with approximately 80 named stratovolcanoes. Their pristine subarctic ecosystems remain largely untouched, thanks to the archipelago’s sparse population of just 8,000 residents—over half of whom live in the Unalaska/Dutch Harbor area.

The Aleut people, Indigenous inhabitants of the Aleutian Islands, maintain a distinctive ancient culture rooted in fishing, hunting, and gathering. Their language, Unangam Tunuu, is the westernmost member of the Eskaleut language family—and the only one not part of the Eskimo branch. The islands’ largest settlement, Unalaska, hosts North America’s biggest commercial fishing port, offering a gateway to understanding modern industrial fishing.

Yet despite their volcanic landscapes, vibrant Indigenous heritage, and maritime significance, the Aleutians remain one of the most inaccessible regions in the US. Their geographic isolation and sparse population mean that, as of 2025, only four airports—Adak Island, Unalaska, Cold Bay, and Sand Point—offer scheduled commercial flights beyond the archipelago, each providing limited and prohibitively expensive routes to Anchorage. A two-hour flight from Anchorage to Unalaska, for instance, costs $600–700, driving many residents to depend instead on the Alaska Marine Highway ferry system. The aging Tustumena ferry, servicing the route, runs only once monthly in summer—and at 60+ years old, it underscores the region’s logistical challenges.

Therefore, the most common way for normal people to enjoy the beauty of the Aleutian Islands is to catch a glimpse of them from the air while flying between North America and Asia.

The limits of human understanding

Even casual travelers who engage deeply with the world soon confront a humbling truth: humanity’s knowledge remains startlingly narrow. Consider the gaps:

- Our models of how the mantle circulates beneath Earth’s crust remain theoretical.

- We’ve never directly observed metamorphic rocks mid-transformation.

- The Grand Canyon’s 1.2-billion-year geological gap defies explanation.

- If humans arrived in the Americas just 15,000 years ago, why do 20,000-year-old footprints persist at White Sands?

- Does Qin Shi Huang’s tomb from 2,000+ years ago truly harbor mercury rivers replicating ancient China’s waterways?

- …

Yet most of these mysteries receive scant attention, as they promise no immediate economic returns—leaving researchers underfunded and technologies underdeveloped.

But perhaps we’ve inverted priorities entirely. Instead of asking, “What’s the practical value of studying ancient rocks or vanished civilizations?” we should instead declare, “We build prosperous societies precisely to enable this work.” The pursuit itself—the act of seeking—is the ultimate purpose. It’s not a means to an end, but one of existence’s purest expressions.

6. Be present and be prepared to be amazed

The allure of distant lands is undeniable, but the wonders closer to home are no less extraordinary—they’re simply hidden in plain sight by the rush of daily life. What we need is not grand gestures, but a foundation of curiosity and attentive eyes to uncover them.

The tide rises twice daily—yet how often do we pause to watch its patient dance? The sun sets every evening, but have you noticed its meeting point with the horizon shifts subtly each day? Thousands of people pass by Wenming Road in the old city of Guangzhou every day, but do they know that the small yellow building is actually the site of the First National Congress of the Kuomintang, and the birthplace of the “First United Front”?

Let’s take Los Angeles as another example. Aside from Disneyland, Universal Studios, the Hollywood sign, and the Walk of Fame, how many visitors would realize that:

- LA is home to the world’s richest Quaternary Ice Age terrestrial paleontological fossils (and the excavation site, the La Brea Tar Pits, is right in the city center);

- The towering snow-capped Transverse Ranges are formed by the “intimate interactions” between the Pacific and North American plates;

- Mt. Wilson Observatory helped Hubble develop the Big Bang theory;

- The LA port is the largest cargo port in the Western Hemisphere;

- The diverse food offerings from immigrant communities across the Asia-Pacific region make LA the most diverse culinary hub in the US

- …

What defines Los Angeles isn’t the glossy theme parks or malls peddled in brochures, but the layered narratives of millions—people, wildlife, and ecosystems—intertwined with a coastline sculpted over billions of years by tectonic collisions and unrelenting erosion.

Awe isn’t measured in miles traveled, but in whether we cultivate the insight to perceive it in the present. Our world is both a relic of Earth’s primordial transformations and a canvas shaped by ancestral creativity. We are grateful to exist in this world on “this side”, standing on the shoulders of giants, gazing at every angle, embracing the endless possibilities in front of us, learning tirelessly on our journey, and igniting our brightest sparks in the limited time we have.

Perhaps this is where the meaning lies.

7. Conclusion

I believe that distant places do indeed offer magnificent views that often surpass the everyday environment around us, as they embody the primal nature that our genes long for, and hold mysterious, unique cultures. We are fortunate to live in an era where technology allows us to reach these once-inaccessible corners of the world.

Yet an uncritical embrace of consumer-driven travel risks blinding us to deeper truths. Books and resources on geology, geography, history, architecture, and other fields often reveal more than any glossy ad campaign. The more we learn, the more we realize that the world is boundless, and no matter which direction we choose to move in, there is beauty to be found. Many wonderful things are actually within reach; the world we live in, regardless of distance, is never short of awe—it just requires the eyes to discover it.

The road ahead is bright and promising. May we walk it with resilient curiosity and open eyes.